To be honest, I can’t remember when the chest pain began. But for at least a few weeks, it had lodged itself behind my sternum.

It wasn’t terrible. It was just there. A discomfort, you might say. And it came and went in intensity, never painful or alarming, but just a subtle, low level pressure that was enough to cause anxiety.

I’d had bloodwork done, and it’d come up discouraging. My cholesterol was high, especially the LDL. And my sugar, too, was high, marking me as prediabetic. I had my doctor’s appointment scheduled for the next week, my annual exam. I figured my doctor would give me hell.

Of course I went online to try to figure the pain out—pain, feeling, whatever you might call it. There was angina. There was arrhythmia—I thought my heartbeat had been off when I’d checked my pulse lying in bed one morning. But there was also heartburn, acid reflux. I’d had my gall bladder removed years back, and of course those attacks—I’d had gallstones, too—mimic heart attacks, so gastrointestinal causes weren’t out of the question.

There was the knowledge, too, from about eight years earlier that I had a leaking valve—something which, back then, didn’t concern the cardiologist I’d visited for a sonogram. I’d seen him before anyone had properly diagnosed the gall bladder. The cardiologist had told me I was too young for heart problems. I was around 45 or so.

At my yearly exam, my blood pressure was normal, my pulse and oxygen count perfect. The doctor put me on an EKG, which took only a minute. She told me I wasn’t having a heart attack. My heart was, for the most part, fine, though she said I had signs of a right bundle branch block, which causes the right half of the heart to beat out of sync with the left. It can be benign, so long as one is healthy. She said she didn’t think that was what was causing the pressure in my chest.

She sent in an order to visit cardiology a few months out and called in a prescription for omeprazole. There is, she said, such a thing as “silent reflux.” The anxiety largely went away, and the prescription seemed to ease the pressure in my chest, too. A friend of mine, when I’d described the symptoms, had said, simply, “Stress.” He recommended I go vegan to rebalance my system. My doctor agreed.

My father had heart surgery when he was my age—I’m 54 now. High cholesterol runs in my family on my father’s side. My mother had congestive heart failure and, eventually, a pacemaker. All these are indications my doctor noted, tapping away furiously at the computer in the exam room. By my sixties, she said, I didn’t want to be in this position.

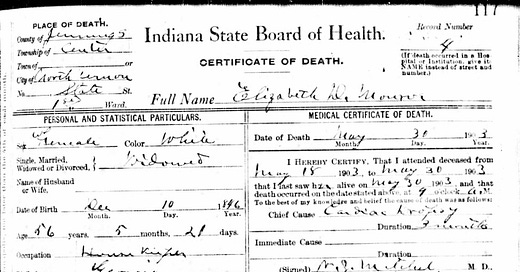

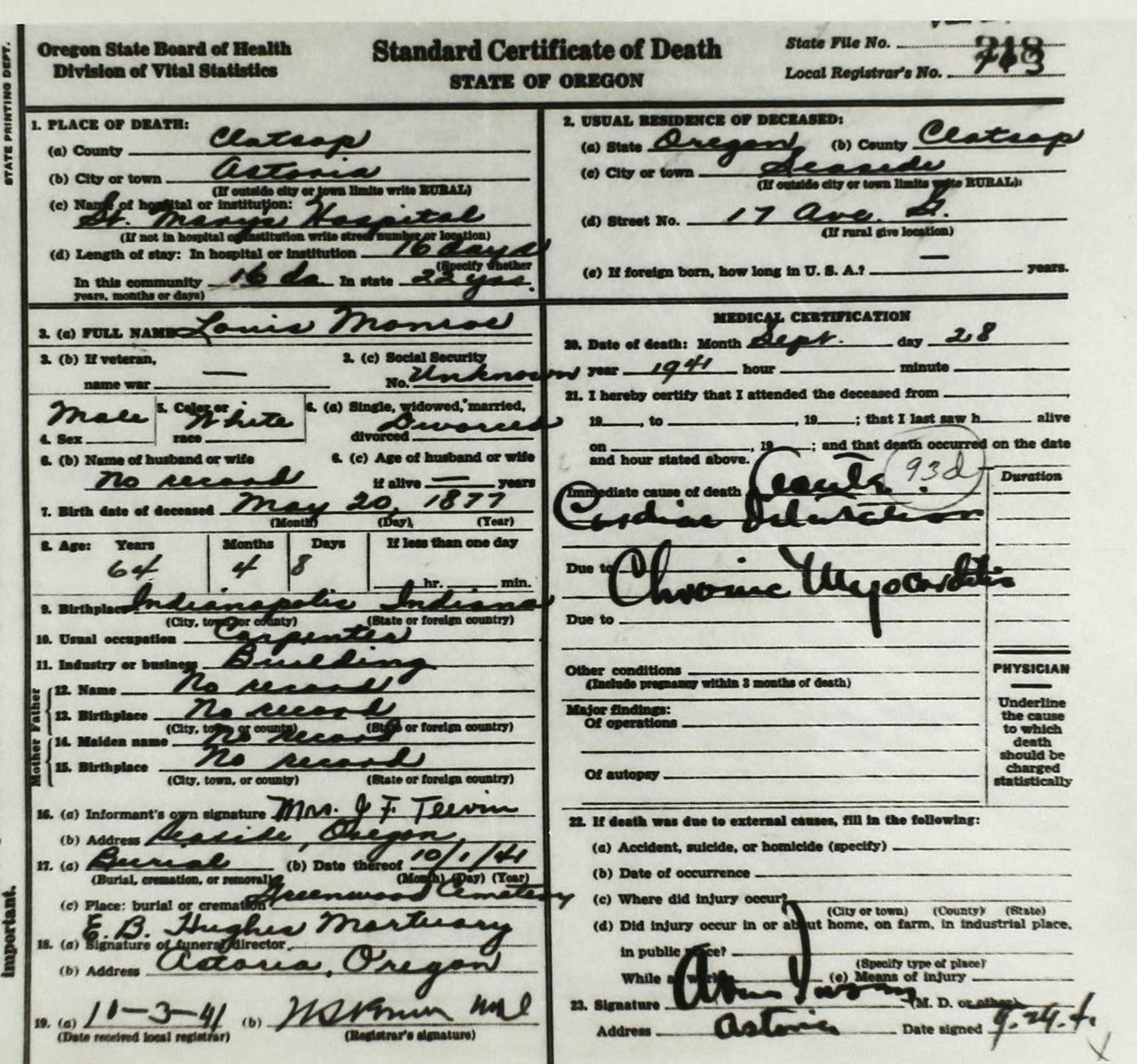

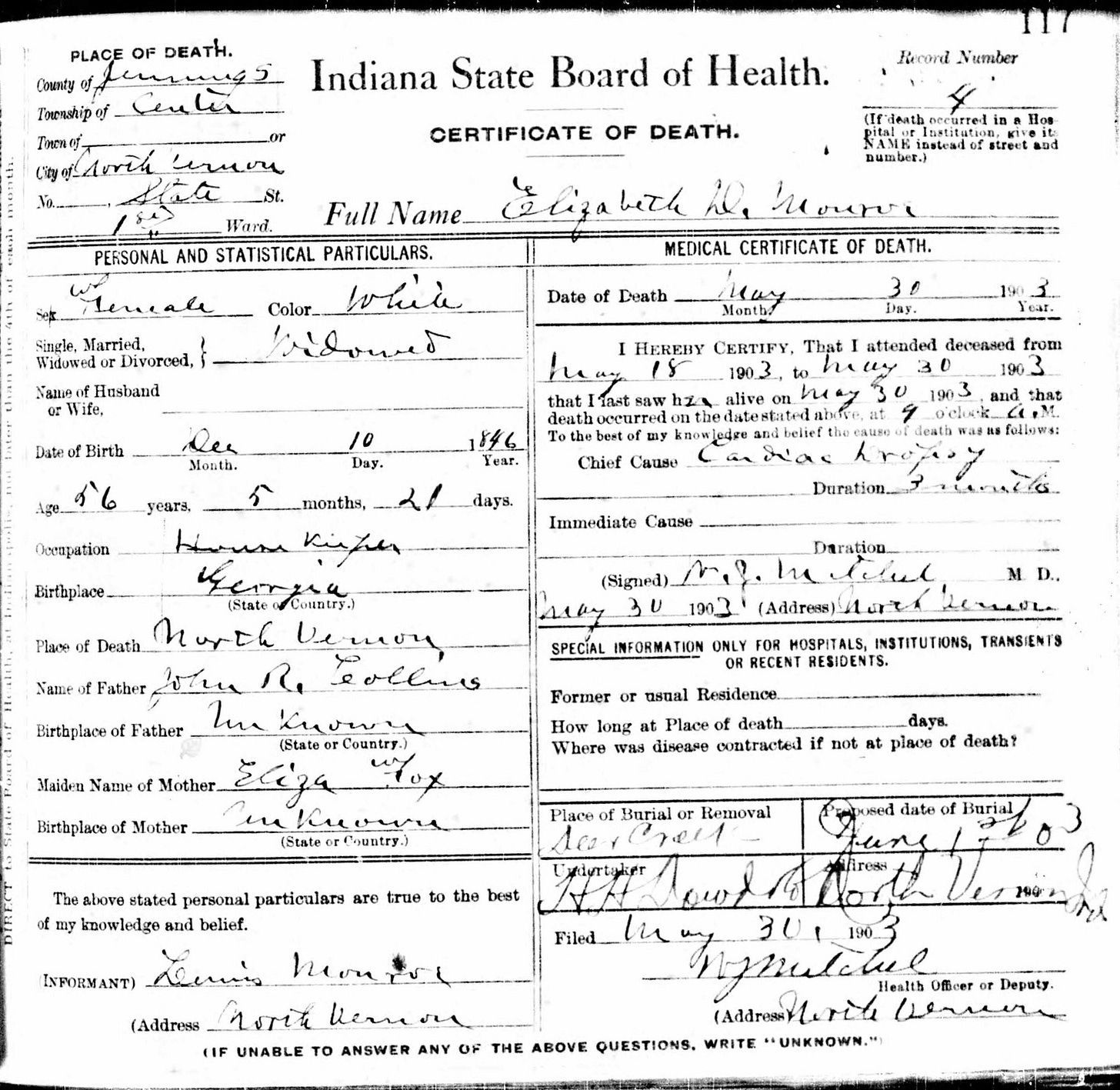

What was strange was that I’d been recently studying the death certificates of some of my ancestors from the early 1900’s. Heart problems, both of them, mother and son. And they weren’t the only ones—I’d seen plenty of documentation of heart failure among my forbears.

I’d always said, the main health problems of my parents were broken hearts. I just didn’t want to be one of them.

There’s an odd thing about the study of ancestry, and it’s this: genealogy is unavoidably a study of death.

Think about it: you’re following the trails of the dead. Reading death certificates, seeing things like “heart dropsy” and “chronic myocarditis.” Reading obituaries, last wills and testaments. Visiting graveyards. It’s a grim venture, at times, even macabre.

And eventually, there comes a point where you might reflect on your own impending death. What, you might ask, will I die of? And when?

If you’re like me, you look backwards and see the deaths of your parents. I do. My father died in the late summer of 2014, my mother at the start of spring in 2022. And before that, I remember all of my grandparents’ deaths.

Health problems of your own begin. For me, the gall bladder was the first scare—those attacks really do feel like heart attacks, gripping and intense. They landed me in the ER. I have what feels like joint pain in my hips, even arthritis in my knuckles. I’m not as energetic as I once was and, as a friend says, you just don’t bounce back from injuries anymore.

In the spring of 2023, I fainted in the mountains of North Carolina. My eyesight went haywire, and I lost all focus. When I woke next to the Cullasaja River—and thank God I didn’t fall in—I climbed back to the road and managed to get an ambulance. I was told it may have been a seizure. I underwent tests until a neurologist told me that it was blood pressure, normally fine, but at that time on the low end, so that any drop in, say, hydration, would mimic the symptoms. Eat more salt, she said.

I’ve not had that issue since, but it did put the fear of God in me. At the time, for all I knew, I had brain cancer. And cancer is something I worry about. My father died of it. And my mother, too, we think had pancreatic cancer, though the doctor declined to test her for it—too invasive, he said. By then, she was already dying, and it would be meaningless to know.

This past summer, I took a job teaching high school English. By then I’d been struggling financially for more than four years. I’d had some work to carry me through the lean months: some freelance writing, some contract work, a semester teaching university writing classes for freshmen. I’d been an artist-in-residence in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, and I’d traveled on grants to Capitol Reef National Park in Utah and to Stockholm and the High Coast of Sweden. I’d had two solo exhibitions of my photography, and I’d even made some sales.

But I worried. I had little put away in retirement. I’d lived for a long time on unemployment, SNAP benefits, and Medicaid. When the unemployment compensation ran out, and when I lost the government benefits, I needed something, desperately. I’m a single parent, my daughter a sophomore in high school. I had prescriptions to maintain—even more now. I hadn’t slept well in years.

Above all this is, of course, my student loan debt. It would be manageable, if not for compounded interest. I took a full-time job to pay down the debt: those loans, plus my mortgage, plus the credit card I used to take my daughter to England.

I knew, having taught before, the cost of full-time work. Nights spent lesson planning and grading papers. Long days—I’m out of the house ten hours each day. I hadn’t even anticipated that the commute alone would have me in the car more than eight hours a week. I became preoccupied with grocery coupons and fuel points. I cut corners where I could, even by cutting meals.

I knew that my writing and my photography would suffer, and they have. My time is enormously limited now. I try to save one day, Saturday, as a strictly creative day. But it’s a lot to pack into a single day: traveling, drafting, developing film and printing, searching for grants and opportunities to fund it all. I’m not ashamed to admit I’ve wept from sheer exhaustion a number of times.

You may have felt this too. How the world often wrenches us from our dreams, from what we imagine we have to offer. Many my age are in similar straits. We worry over our retirement accounts, if we have them at all. We can’t depend on a future promise of Social Security. We feel our bodies failing, the aching joints, the fatigue, the persistent headaches, or, worse, the blooming pressures in our chest.

I visited the doctor for the first time in a long while, and it took great courage to tell her that I’d begun to feel chest pain.

This March, I went to the hospital for a CT scan. This, I was told, would give me a definitive answer, as it was my arteries that would be scanned. You may know the anxiety one might feel, waiting for an answer, being that close to an understanding.

I arrived at the hospital at seven a.m., as directed. I was soon in a bed behind a curtain, an IV in my arm, blood drawn. The nurse told me straightaway that the blood test showed that there was no plaque or calcification—a good sign, she added.

The scan took only minutes. I was asked to hold my breath; I felt like I’d been holding it for months. My body was flushed and warmed by the radioactive iodine I was injected with. I thought of my daughter.

I would not be released, I was told, until my blood pressure returned to normal. Instead, it dropped. I had to get to work, I said. The nurse kept tilting my bed back, to draw the blood to my head. When I was released, all I could do was wait for results.

When they came back, I swooned from relief. I was completely in the clear. The report literally said, “unremarkable.” I couldn’t believe it. At once, I saw a future, brighter than I’d seen in months.

Still, even now as I write this, I think, I’ll die of something. It could be anything. A form will be drawn up that perhaps someone will look at one day, and my name, like those of my ancestors, will merely be ink on paper, with little more than conjecture as to what kind of life I lived while I was here.

I’ve long known, especially since researching my ancestors, that this is one of the main reasons I write: to preserve myself. To tell how it was, the way we lived.

Like this, something I texted a friend: I was sitting on the couch in the evening, grading essays, the shades up and the darkness outside covering the dogwood blooms. I heard a mockingbird begin its repertoire, close and fierce. I thought about how they will sometimes sing in the dead of night in the full moon.

I’d heard them sing in the moonlight before. And here I was to hear it again. What a gift, I thought, to be alive to witness. And if I was lucky, I’d witness something tomorrow. Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow.