Exhuming

"It was the best part of you that you buried."

Five years ago, I went looking for a grave that I never found. I know now it can’t be found—the girl, she was buried too long ago, more than two hundred and twenty five years. I left the graveyard and went north. Those graves, the soldiers, the pioneers, they were behind me when I edged the car to the highway’s shoulder just over the bridge that spanned Pine Creek. What was I looking for? Where did I think I was going?

And what did I feel then? Excitement, perhaps. That this was a kind of adventure, and I was a long ways from home, a two-day drive. I must have been so immersed in the moment that I had no self, no history, not even a name.

After I shut off the engine, I did two things, I think. First, I went to look at a signboard that stood beside the road, at what was the entrance to the gorge. An old sign, like something I might’ve seen as a child, growing up only a few hours north of here. The sign probably was that old, unchanging, and this may have been what attracted me. That sign advertised not only the wineries and campgrounds that were further ahead—one was called, Happy Acres Resort—but also advertised what was lost. That time, those years. Places my father would take me. Me and my family.

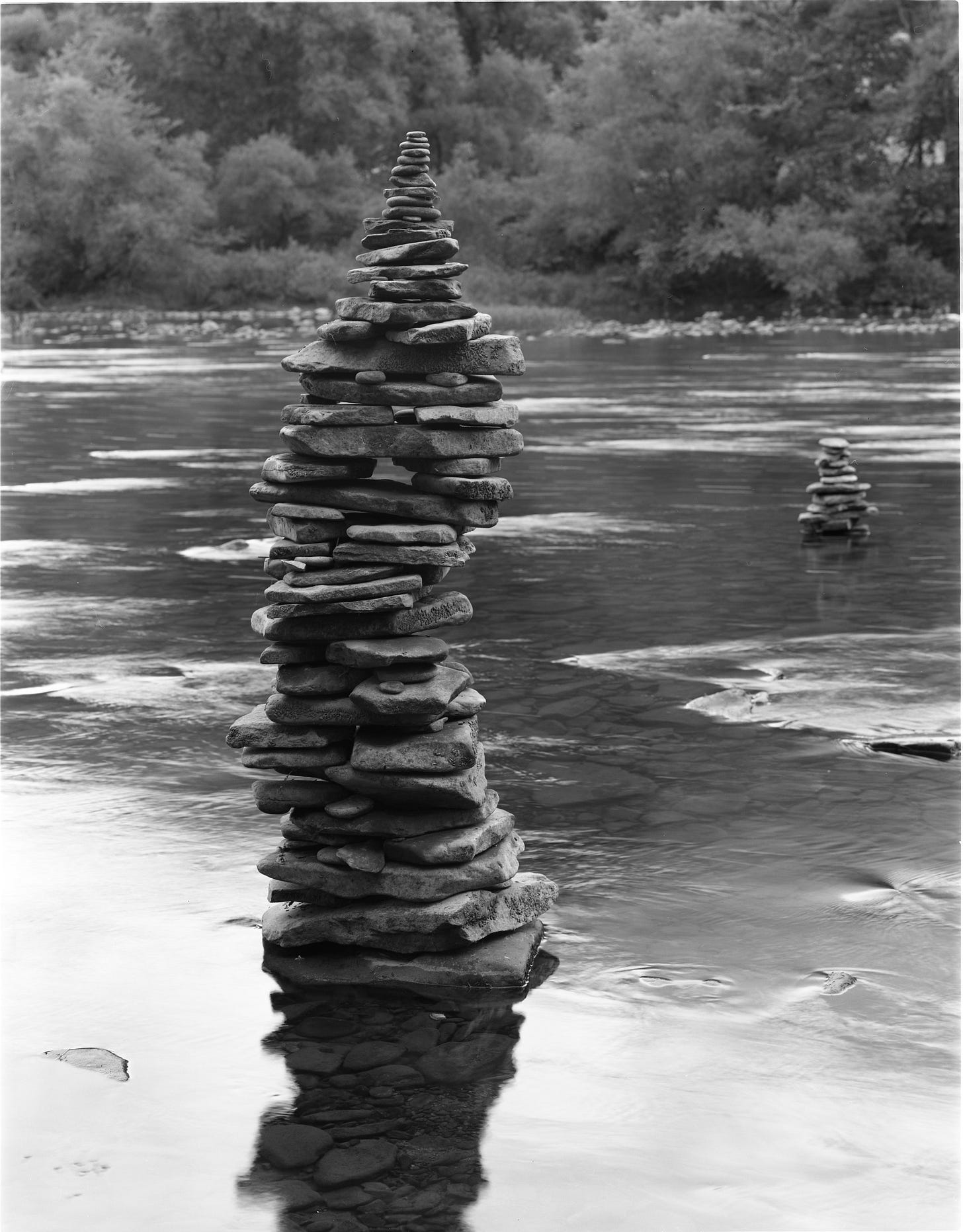

Then, I imagine, I walked back to the bridge. I wanted to see the creek. Pine Creek is not what I think of when I think of creek. It looks more like a river, like the Chemung River, which ran close to my house, the house my father rented starting in the winter of 1981, when I was in fourth grade, when we moved to Elmira from New Jersey. The river looked like this creek, and the signboard looked like 1981, when there were still ice cream shops in West Elmira, movie theaters downtown, and antique stores in the countryside.

I looked at the creek and tried to imagine my ancestors pushing their way upstream in canoes. I tried to imagine what they saw in these hills, what would have been deep forests. Did the darkness overwhelm them the way it had so often overwhelmed me?

What did I feel then? Nostalgia, surely. Is nostalgia a feeling, or an idea? The warp of memory is always fraying. It falls apart in your hands, but it takes a lifetime to see that. It has taken me a lifetime to learn this. Fifty years. That was my fiftieth year, standing there above the creek. No one on the road but myself.

In that moment, I would’ve set aside the many things I’d thought defined me. Or else simply forgotten about them, unimportant pebbles I dropped over the railing. That I was a single parent, a divorced man. That I’d been laid off from my job only a few months before. That a relationship I’d had for a few months crumbled by the end of winter, that I’d seen this brief affair as a last chance, a bit of luck that had soured. The unemployment checks, the EBT card, the ballooning student loan debt. The fear.

I was angry. Angry at the world, angry at myself.

Upstream, I was headed for the hotel. The hotel, I understood, was on ancestral land. The Hotel Manor, it’s called. My ancestor had landed his family on the shore there in the late autumn of 1791, in the cold and falling snow, the cabin before him unfinished. His daughter left under a mound behind him.

There are things buried behind me, too. There are children I’ve left behind, the children who would have recognized these signs, who would’ve marveled at this river, the osprey I saw drifting over the current. Those children would’ve recognized these hills, though they didn’t yet know what had carved them, knew nothing of glaciers, or plateaus, or even the names of trees or the bedrock.

Each child a page in a book authored perhaps not so much by me as by circumstance. Each child like a day born at dawn and gone by nightfall.

This is Pine Creek. These are the Allegheny Mountains. This is the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the watershed of the Susquehanna. Mountains made of sandstone, towns built on lumbering and coal. What I don’t know is who I am anymore. Let the trees judge me: outside of this gorge, beyond the lodge where I’ll sleep a few nights, I’ve no idea where I’m going or when I’ll arrive.

I’d begun this journey through genealogy because of my father. Genealogy is a journey in that it’s a narrative, a story. And therefore a myth. I was there in that gorge to forge a new myth for myself. The story of a son who takes what his father has gifted him in order to fashion something of it. A life I could believe in. A son of many fathers, in fact, and many mothers. I wanted, as maybe all men do, to prove myself, the way one proves a last will and testament.

I’d seen many of these wills in books I’d found, written by men I owe my life to by sheer stint of their survival. I marveled at this. That these men and women had survived wars, plagues, famines. They’d survived ocean crossings. Long enough, at least, for another generation. It made fate seem comprehensible. It made my life feel like a miracle.

I wanted life to feel miraculous again.

Mostly, I wanted to write a book. I’d had the idea to write a book about the land I’d come from for something like twenty years. These are interests—history, ancestry, geography—that I’d inherited from my father. I knew that, even then. So I went to Pennsylvania, into those mountains, to gather notes. To go to libraries, courthouses, historical societies. To visit the small churches and their bundles of graves. To try to make sense of who I am, who I was, and what I could be.

I wanted, in short, to complete the work of my father. To add to the notes he’d left me, to make sense of the books I took from his house after he died, the photographs he’d collected of people I never knew. I wanted to find a thread in a time where my own life’s thread felt it had been broken, severed.

This, I came to find, must have been the root of my father’s obsessions with genealogy: he must’ve felt adrift. He, too, was divorced. From all accounts, he seldom called his children, me included. What was he afraid of?

I’d come to those mountains to find what I was afraid of. And I wanted to find the courage that I imagined my ancestors—my father, included—must have relied on.

On a Friday morning in early August, finishing my coffee, I saw a clip from the movie Ordinary People. It was a movie I’d never seen. It came out in 1980, the year before we left Jersey. The clip was a monologue by Donald Sutherland, who played the father of the boy who drowned, and also the boy who tried to commit suicide. He’s talking to his wife, and he says to her, “It’s as if you buried all your love with him…”

And then he says, “It was the best of you that you buried.”

That struck me. I thought of all the graves I’d gone looking for, including the girl—who was also drowned, at the mouth of Pine Creek. The body that’d been exhumed by a farmer’s plow in the Catherine Valley. The headstone of John Tomb I’d set upright in the little graveyard behind the ruins of a Methodist church and a hunting cabin. The graves I couldn’t find in Indiana, unmarked, probably in that plot along the Muscatatuck River.

I thought about my own divorce, book-ended by my parents’ deaths. I thought about how I’d stopped feeling like myself. As if I’d lost something. I thought, in all that grief, I buried the best of me. I did this in order to survive. To pay the bills. To maintain my composure and not lose my mind.

And what I was doing, as if I were living out a myth, was looking for the bones. The body. The boy.

I’ve found something. I don’t fully understand its dimensions yet. I’m like the teenager who followed the plow, holding a skull unearthed among the cobbles of stone, holding it out to the farmer, asking, What do you want me to do with this?

This summer, I traveled to Spain. I stood before the self-portrait of Dürer in the Prado. I walked the Barri Gotic of Barcelona, the Casco Viejo of Bilbao. This opportunity came of a grant I’d been awarded, and I had to remind myself—to insist to myself—that I’d earned this by my work in photography over the years. That this was my life. My karma, really.

Much happened in the five years since I drove to Pennsylvania that first time. I’d been an artist-in-residence in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. I’d held two exhibitions of my photographs and won several grants. I’d published numerous times—I wrote about the Civil War battlefield in Kentucky where two of my ancestors fought, and of the buffalo trace, nearly forgotten, that passed within a mile of my house, or the creek through my neighborhood that had slowly faded from nineteenth century maps and existed now only as running water in storm drains. I taught a semester at the university and, finally, secured a job teaching high school in Oldham County. Most of this was after my mother died at the start of spring in 2022.

I live alone. My daughter is with me half the week but, save for summer and breaks, I see so little of her. As for romance, I’ve gone on a few dates, but nothing came of them. I get lonely, of course. I take long walks through the neighborhood, down to the community gardens, which today blooms with sunflowers. I work in the darkroom when I can.

Mostly, I find myself tired. I tell myself, I’m exhausted. For years now, my sleep has been interrupted. My debt hangs over me, a sword of Damocles, marring whatever future I imagine. Like many in my generation, I have little saved for retirement—if retirement is even a possibility. And my daughter will graduate in less than two years; then what? Will I go on just mowing the lawn, shopping for one, sitting beside the window in the evenings, waiting? Will I ever be in love again?

It’s not easy to write a book in light of such worries. I’ve made this newsletter as a way to stay focused, to explore these lives I discovered in corners of libraries and the web. Life intrudes, of course. The demands of what I owe are always close. And teaching, as all teachers know, is consuming. It devours my time and my energy in equal measure. The time to write has dwindled.

The genealogy: I’m beginning to leave it behind me. Sure, the idea for my book still flits around me like a ghost. It’s a manuscript made of ghosts. I resign myself to knowing it may never get written. Perhaps, on behalf of the dead, I’ve said enough. To find new subjects, new names, and more, to visit new places, is beyond me most of the year. Too many responsibilities. Too many obligations.

I may have made my father proud enough.

For the past several weeks, I laid out a story in my newsletters—the strange story of the Monroe’s in Indiana—that covered my time in Spain. Now I’m back but drained. Before me is the new school year, which I begin in only a few days. I’ll go back to the commutes, to the meal making, the housecleaning. I have other responsibilities as well: a story to be written for a magazine, a small exhibition to curate, framed photographs of my own to deliver to a gallery in New Albany.

If I’m to maintain this story, I know that I must write from the heart, from what is troubling me—or inspiring me—in my daily life. Sometimes it may be the subject I started out with: genealogy. But I’ve found that this has become clothing that’s shrunk around me. I’m constricted.

But to write what’s on my mind, publishing every two weeks—perhaps even monthly—that seems realistic. A way to work things out, crafting a voice that might reach what readers I have or have yet to find. This is my resolution.

When I talk on the phone to my good friend, Andy Budor, who lives in Portland where we’d initially met almost twenty years ago, we talk of living a sane life in a country where hostility and inflation have only swelled. I speak of my two hundred dollar grocery bill, twice what I usually pay, in the same breath I speak of the homelessness in the streets. We talk of mindfulness, of Edward Weston, of Spain, of the history of Tibetan Buddhism (my friend is, to my mind, a Buddhist scholar, though he’d demur in calling himself that).

A

I would ask that you accompany me on this journey. Think of it like this: I’ve now left the gorge in the Alleghenies, the shore of Pine Creek, the landing where Jacob Tomb stepped out of the canoe and into his new life. I’m bound elsewhere, now. The house may be unfinished when I arrive. It may be winter, I may be hungry, but like him, I’ll build a fire. I’ll finish the roof.

Like him, I’ll go hunting in the forest.

Then let me reintroduce myself: My name is Sean Patrick Hill, and I was born fifty miles from the mouth of Slate Run to an engineer who taught me to love history and a secretary who taught me to be kind. I’m a teacher of writing and literature. I’m a photographer, an artist. A father to a daughter soon to be on her own. I live, for now, in a city in the valley of the Ohio River.

You find me standing now in the turned-over field, asking, What do I do with this skull?

I have a story to tell. I’m canoeing upriver to find it. In each of the graves behind me, I’ve left a few words covered over with a handful of earth. In these paragraphs, you lay your ear to the ground and listen; I’m recounting my travels—to Pine Creek, to Spain, to the sunflowers at the end of the road.

I am going to reclaim my life, to unearth the love I left buried, to recover the best of myself and present it, finally, to you. It’s all I have. I want to believe it’s enough.