In Sickness Time

Old Goodwife Cutter, the Cooper, and Me

Often enough, I doubt what I’m doing.

This job I currently have, teaching high school English, often troubles me, not so much because of the workload—though that, too, is extensive—but because of the moral quandaries it’s left me with. Is this truly what I want to do? Is this the purpose I see myself fulfilling?

And of course I judge myself harshly at times.

One of my ancestors was a schoolteacher. This was before the Civil War, and the man was my third great-grandfather. His name was Richard Lord Hill, and he was, at the time, a single man courting my soon-to-be third great-grandmother, Julia. He taught in what was then known as Knoxville—now the north side of Corning—and later, up around Lake Ontario. I’ve begun to read the letters he wrote while he was teaching.

When I read the old accounts of people who lived centuries ago, it gives me a frame with which to describe my own life. I pay attention to the descriptions in old texts: what were their troubles? How did they describe their towns, their villages? What were their occupations, their responsibilities? Where were their memberships, what churches and guilds?

I find that I’m already historical, in a sense: someone a few hundred years from now might read my clothbound or leather-wrapped journals, or a clipping from the Bend Bulletin, an op-ed I wrote for the Lexington Herald-Leader, or even a poem I published in an obscure academic journal, and they would see—more than we could today, in many cases—the context of my life.

The prevalent beliefs of our time, for example, might shine through clearly. Were someone to read about me, they might assume I was unorthodox, that to be so was not uncommon. I belonged to no church, at least not as an adult. They would discover, as well, that I’d had a number of careers: as a high school teacher, a business writer, a college instructor, with a scattering of retail jobs, freelance assignments, and volunteer work. They’d see I was a published poet, an exhibiting photographer.

But this would only relay the most rudimentary understanding. If someone were to get a hold of the journals from the time I lived in Oregon or Kentucky, they would hear, to my chagrin no doubt, my “sad complaint.” It’s for that reason I often think of burning them—ceremonially, of course. I would see this as liberation.

Someone in the future, though, might see this as a shame. But to have access to my thoughts, scribbled on my handwritten pages, they might see as a blessing. They might imagine me on those cold mornings, in my robe, a cup of coffee at hand, writing by the light of a single lamp, the hum of a sixty watt bulb.

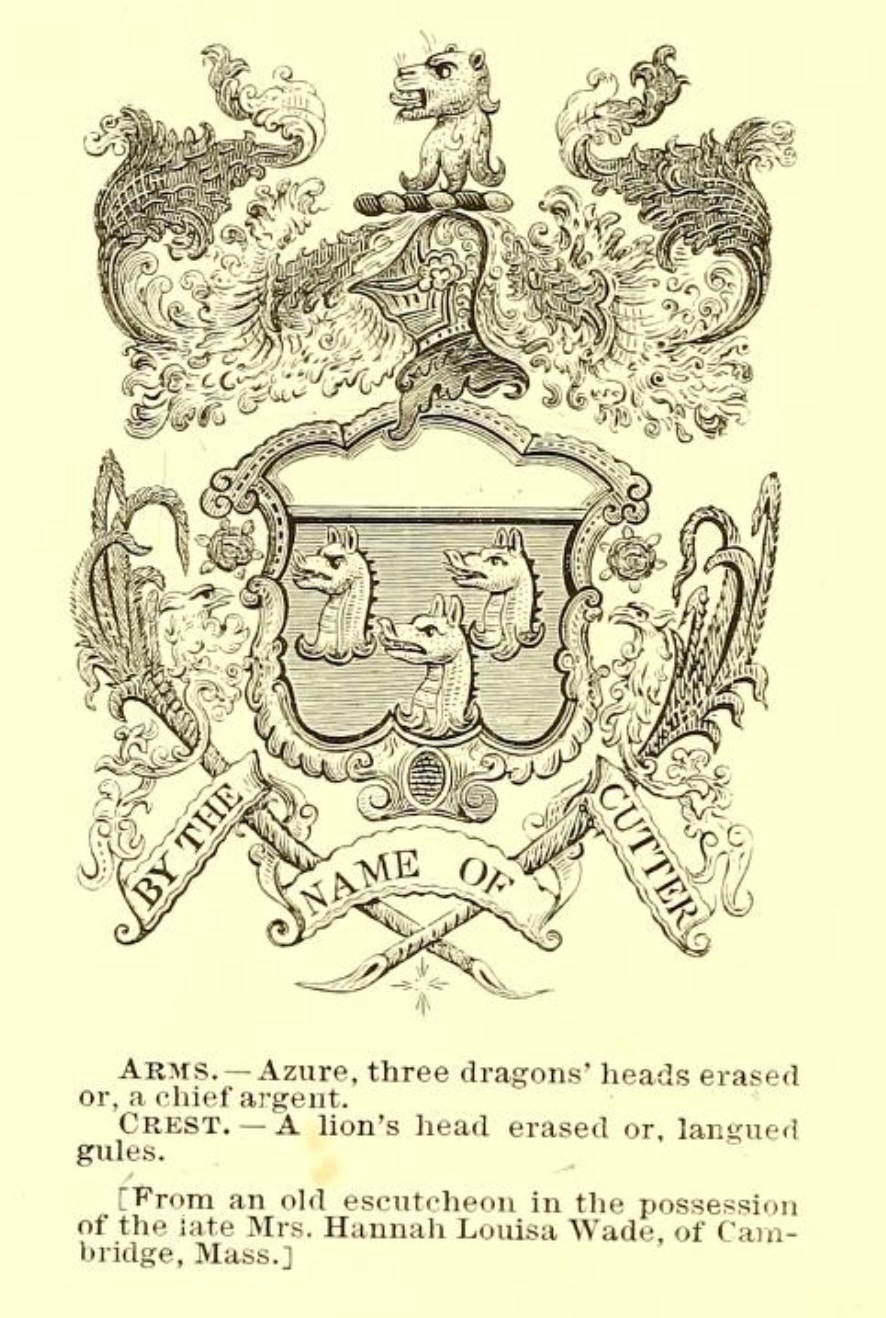

I consider this when I read the words of Elizabeth Cutter, born sometime in perhaps the 1570’s on the frontier of England, perhaps the Tyne and Wear country. She bore the same name as the Queen, and she would have lived among shepherds and coal miners, the chief industries of Newcastle in that century. I’d have to turn to history books to get a sense of the life around her as she grew and made her way to the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

“I was born in a sinful place where no sermon was preached,” Elizabeth Cutter told the minister of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Where that place was, we don’t know; somewhere in England, probably along the North Sea. We might imagine it as a small village, a settlement with no church. Perhaps she lived on a sheep farm, or maybe her father was a miner.

Elizabeth never knew her father, but her mother sent her to a family in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where she stayed some six or seven years with “a godly family.” But despite her time with people of good influence, Elizabeth said that she’d by then broken two commandments: taking the Lord’s name in vain and keeping the Sabbath day holy.

She went on to stay with another family that was “carnal,” she reported, and “afterward followed with Satan.”