I’ve been working on this post for a number of weeks, and as I write it, the main news is that the American military bombed Iran.

In light of such unsettling news, I struggle to make sense of what I’m doing at all, what my purpose is. Or, what the purpose of writing such posts at all can be in light of all that’s going on in the world.

One thing that struck me from John Berger’s BBC series from 1972, Ways of Seeing, was the idea of juxtaposition we see in the media, images of the atrocity of war coupled on the newspaper page with advertisements.

In between each page, as John Berger says, “There is such a fissure, such a disconnection, such incoherence, that one can only say this culture is mad.” It doesn’t matter if it’s a page from The Sunday Times Magazine in Berger’s time or a webpage from today: the disorientation is still very much here.

What I want, then, is to write to resolve this incoherence, or even to write against it. I want what I am investigating to speak with what is happening.

One thing that came up while I’ve been investigating the family line I’ll be writing about and posting over the next couple of weeks is the Civil War. It burst into this story when I didn’t expect it.

I’ve said this before, but it’s worth repeating: I’m often struck, when looking at my ancestors, by the idea of how they survived their times. Their lives, whatever I can see of them, help me to get perspective on my own.

When I arrived at the Jennings County Library in North Vernon, Indiana, Ed Keller, the genealogist librarian, was already looking for the newspaper I needed to see.

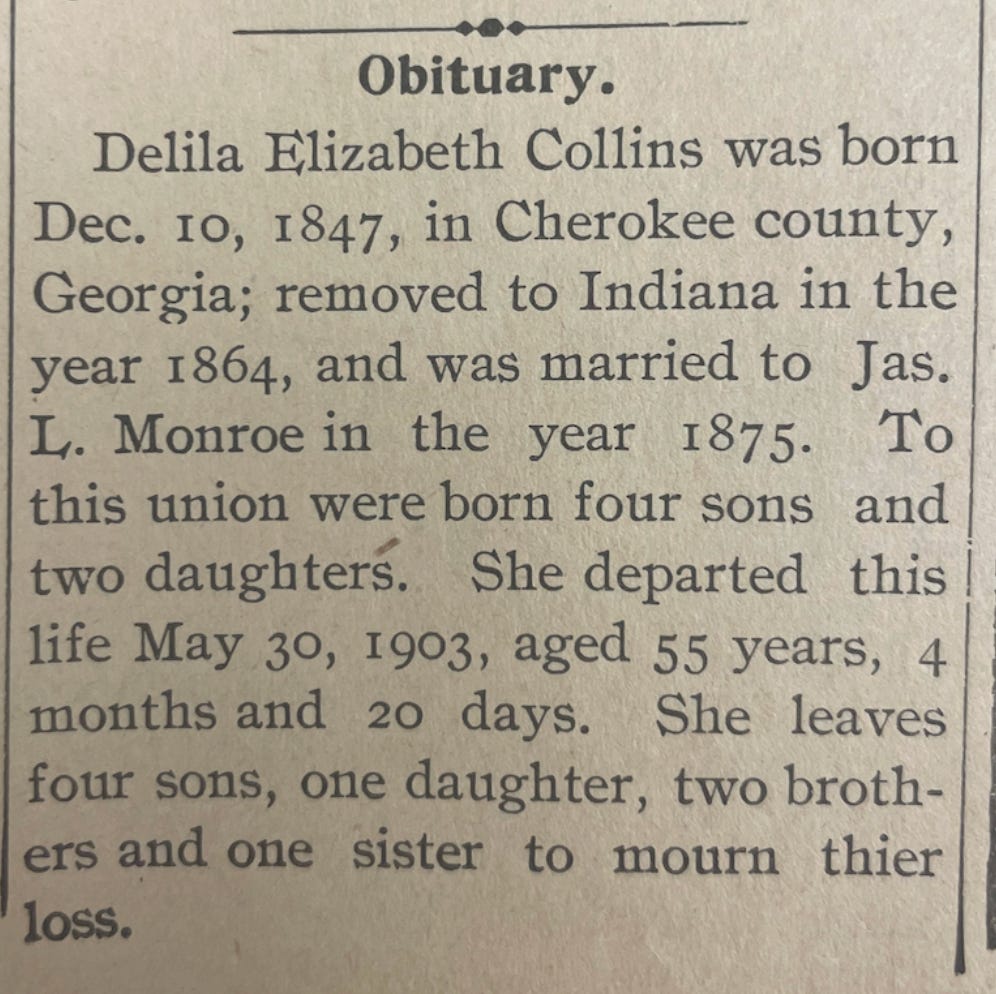

He’d gotten a call from Sheila Kell, the retired county historian I’d spoken to on the phone that morning. He returned from the archives with the bound issues of one of the county’s oldest newspapers, The North Vernon Sun. In it was the obituary of my third great-grandmother. It read,

“Delila Elizabeth Collins was born Dec. 10, 1847, in Cherokee county, Georgia; removed to Indiana in the year 1864, and was married to Jas. L. Monroe in the year 1875. To this union was born four sons and two daughters. She departed this life May 30, 1903, aged 55 years, 4 months and 20 days. She leaves four sons, one daughter, two brothers and one sister to mourn their loss.”

I suddenly had a wealth of information. First, I had more of a sense of where she was from, specifically; Cherokee County is just north of Atlanta. However, there are inconsistencies; in a marriage record of one of her sons, drawn up after Elizabeth died, it stated she was born in what looks to be Cartersville, Georgia, which is in Bartow County, to the west of Cherokee.

In genealogical investigations, one gets used to these problems. In my Indiana searching, there would only be more. The marriage date, for example; the recorded date in the county records is August, 1876. Still, this was a good start. However, one key item left out of the Sun’s obituary: where she was to be buried.

On the Find A Grave website, she was said to have been buried in the Tea Creek Cemetery, nearly ten miles south of town. I drove there some months prior and couldn’t find her grave. Granted, there were many unmarked stones, but I found it odd, too, that she should be buried at a church that was relatively far out in the countryside, especially in 1903.

The official Indiana death record posted online, on closer inspection, says what looks like Deer Creek, and this was confirmed when I drove to the Jennings Health Department and flipped through the pages of the old ledgers there, where the handwritten death records were kept—it repeated, Deer Creek. The problem was that no one could tell me where this cemetery was.

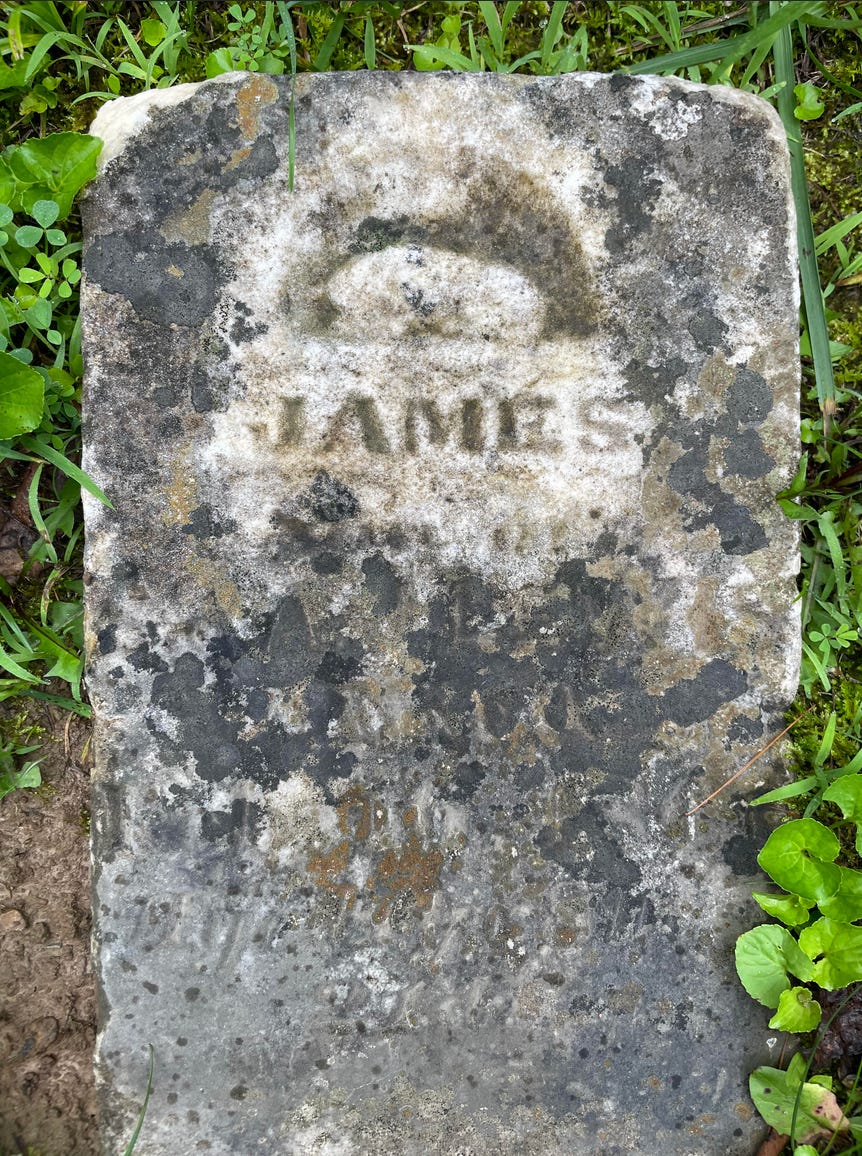

Some phone calls revealed that the one Deer Creek cemetery that was evident in the county was, in fact, an African-American cemetery. Sheila Kell did some investigating and found that there was another that used to be called Deer Creek, but Elizabeth’s name did not come up in the listing on the find a Grave website—today it’s known as the Summerfield Cemetery. Again, I found this odd; a grave as recent as 1903 should not have vanished so easily. Stones from the 1800’s often disappear, especially those from before the Civil War. But this missing stone, in my experience, was a mystery. Where was she?

The main reason I wanted to find her grave was to find her husband, James Lee Monroe. I could find no grave listing for him either, nor even a date of death. His name, at least when I first went through the ledgers in the health department, was not listed. If I could find his stone, I imagined, I could begin to solve a puzzle that had plagued me for a number of months: were my ancestors descended from slave owners?

Next time, join me to continue this search.