Last week, I described my initial plunge into searching through my Monroe family line—this was my mother’s line, born a Monroe before she changed her surname marrying my father. I’ve been trying to ascertain whether we’re descended from Andrew Monroe, an ancestor of President James Monroe and the patriarch of a family of slave owners.

In my search for information on James Lee Monroe, my third great-grandfather who lived, for the most part if seems, in Jennings County, Indiana, I had to begin with the person for which, at least at the outset, there was abundant information: his wife, Elizabeth Delilah Monroe, née Collins.

In the 1900 U.S. census for Jennings County, which was compiled on or about June first, Elizabeth Monroe, the wife of James Lee, is listed as “Head” (as in, the head of household), and the “4C” scribbled above it refers to her having four children still in the home: three sons, Marion, Edward, and Dalby, and one daughter, Alta, all ranging in age from ten to nineteen. Her husband, James, was obviously already dead. There was, of course, the offhand chance that he’d left the family, but in a marriage that spanned the late nineteenth century, I would think this unlikely.

In that 1900 census, Elizabeth’s birth date was listed as December, 1847, and the birthplace, Georgia—so far, so good: this matched the materials I’d previously found. Her parents, interestingly, were both listed as having been born in North Carolina—I’d found indications of a lot of Monroes who came from Rutherford County in that state. She could read and write, as the checkmarks in those boxes suggested. The census also indicated she rented a house in town, North Vernon, part of Center Township, in the city’s third ward.

The rental struck me as odd. In past censuses, James had been listed as a “farmer.” Had there been a family home at some point? If so, what happened to it?

Just below Elizabeth’s family entry is that of Lewis Monroe, the head of household, as well as his wife Dora and their sole son, my great-grandfather Arthur. Lewis’s birthday was May, 1877; his age, twenty-three. My great-grandfather, born in November of 1898, was only a year old.

Lewis, my second great-grandfather, was listed as having been born in Indiana, which makes sense. According to the census, Lewis also rented a house, and his occupation was “Tinner,” what looks to be a tinsmith. His mother, Elizabeth, was listed as having been born in Georgia, but his father was listed as having been born in Kentucky.

The birthplace of the father conflicts with other records that say he was born in Indiana. This was the track I was trying to blaze: walking the family backwards into Kentucky and, further, into North Carolina and, ultimately, Virginia. So what was the nature of this error? A lapse in memory? Clumsiness?

If I could ascertain the birthplace of James Lee I could potentially narrow my search, especially if I could nail down the county he was born in. That could open the doors to other censuses, courthouse records, and so on. It seemed critical to do so.

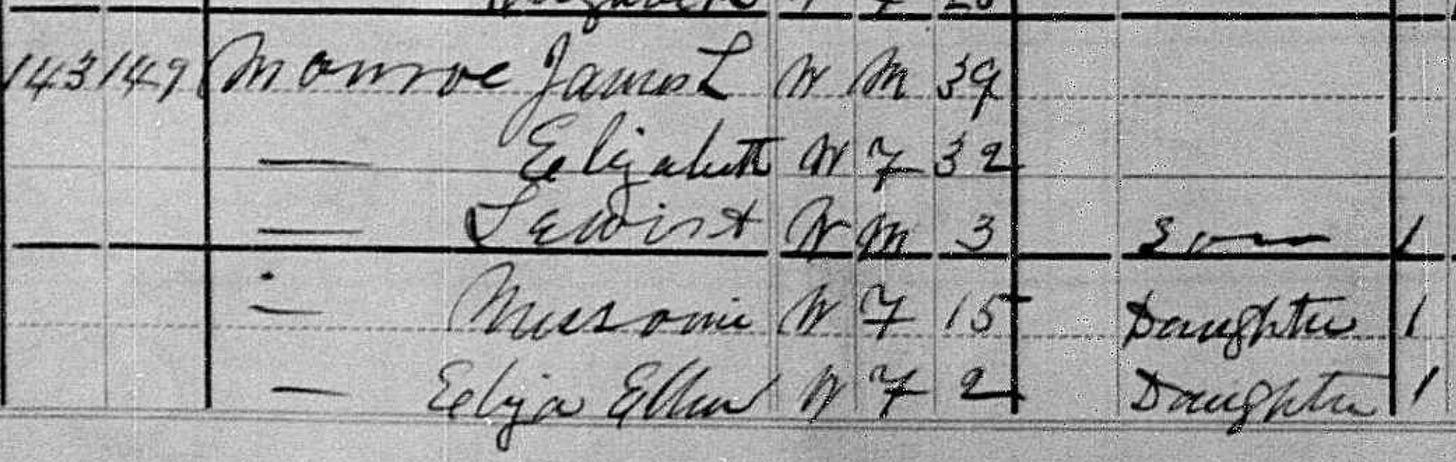

Because the U.S. census of 1890 is largely lost, I need to back up to the 1880 census, when Elizabeth was thirty-two, a “housekeeper,” and clearly married to James L. Monroe, who was thirty-nine—putting his birth as 1841 or so. Their son, my second great-grandfather Lewis, was three years old. Interestingly, James is listed as a farmer. A fifteen-year-old daughter, Missourie, was reported “lives at Poor Farm.” All are recorded under “Center Township.” Again, here, James’ parents are recorded as being born in Kentucky, and Elizabeth’s in North Carolina.

No one I’d run across, apparently, could ascertain when James died, exactly. It must have been between 1880 and 1900, and one of the most unfortunate things—what would have helped narrow things tremendously—is whatever might have been documented in the 1890 census, most of it destroyed in a fire in 1921.

Then I find something surprising. I find a document online where my second great-grandfather, Lewis, applied for Social Security in October of 1938. His birthday is listed as May 20, 1877, which is accounted for. But his birthplace seemed odd, so I looked it up—apparently, he was born in the town of Hope, in a small township in Bartholomew County, Indiana, a county that adjoins Jennings. But his marriage record from April, 1898 says his birthplace is—from what I can tell—St. Louis, Indiana, which looks to have been a small community to the northwest of Hope. Farm country—no wonder James’s occupation was listed as “farmer.”

A quick internet search shows a “James Monroe” on the 1860 census for Bartholomew County, in Columbus, which is the county seat. There are other Monroe names there, as well. The 1850 census, however, shows none. I am aware, by now, that “James Monroe” is not an uncommon name. This only adds to the confusion.

In another Social Security application from 1938, another of James and Elizabeth’s sons, Marion—with Elizabeth and James both specifically named as parents on the form—suggests that by this son’s birthday, on February 22, 1881, the family was living in Jennings County. That corroborates the 1880 census.

What happened to James Lee in those intervening twenty years, until the turn of the century? What I’m trying to ascertain is the name of his father, which is purported to be Edward, the only evidence being this: In the 1850 census, there is an Edward Monroe—who is designated as having been born in Kentucky—living in nearby Jefferson County, in Republican Township, just north of Madison, Indiana, which sits on the Ohio River across from Kentucky.

In this census, Edward looks to be 58 at the time—admittedly, the handwritten age is not easy to decipher, and it could as well be 38—and his occupation is a cooper. There is no listing for a wife. Among the four children listed with the Monroe name is one James, 14 years old, listed as born in Indiana.

This puts the date of James’s birth back to 1836, though this conflicts with the age of James Lee in other documents, which would set his birth year to 1841. I pointed out this fact to Ed Keller, the genealogy librarian in Jennings County, who just shook his head in understanding. This is one point of the census: There are often errors. Or else, of course, these are two entirely different people.

On this very same page in the 1850 census, names are listed with their middle initial, but not James; that middle initial of “L” would make a world of difference. One goal, then, would be to find an earlier census, though the problem with the 1840 census—and all those preceding it—is that they do not list the names of children—or typically women, which means their wives.

In a simple Internet search, I find a transcription of the 1840 census for Republican Township. There are many Monroes: Ausburn, Philip, Jefferson, Melissa, Michael, two Williams, Whitson, Susan, Abraham, George, Landal, Byram. I find, though, in the Milton Township census of that year (Milton is to the east of Madison) a James Monroe, as well as a John and Lyman.

I find that the name Monroe—and Munroe—begin appearing in the 1820 census of Jefferson County. On this webpage for the Genealogy Trails History Group, at least, that’s as far back as records go.

These are the numerous issues when trying to find ancestors from the early half of the nineteenth century: the older they are, the less detail they describe. Names begin fluttering off, like the bits of yellowed paper that flake away from the old books I handled in the Jennings County Library.

On June 19th, I drove back to the courthouse in Jennings County. I had been waiting eagerly to see the marriage record of James L. Monroe and Elizabeth Collins. The main thing I wanted to see—and hoped to see—was the name of James’s father. An online scan I’d seen was completely marred and illegible. I hoped this time to set things in order.

I was entirely surprised to arrive at the courthouse that morning to find it closed. Juneteenth. I hadn’t even thought of that.

I drove under the railroad tracks and headed north toward what was purported to be the old Deer Creek cemetery. The final stretch through the Selmier State Forest was a gravel road following the Muscatatuck River. I found it easily enough.

The triangular plot of ground, bound by an ancient wire fence, was filled with gravestones that were broken, worn, and unreadable. There were the graves of the poor: simple, irregular slabs of limestone, most blank, one etched by hand. I’d later find a book in the library that said plots here were sold for $5 at the time my ancestors died. There was, of course, no trace of the Monroes here—nor were they listed in that book, published in 1982; even then, there were unmarked graves, the author wrote.

I went back to the Jennings County Library to get help from Ed Kellar.