Looking for James Lee (Part III)

"Only pity is to be felt"

This is the final segment—at least for now—in my searching related to my third great-grandfather, James Lee Monroe, born in either 1836 or 1841, in either Indiana or Kentucky.

When I returned to the Jennings County Library in North Vernon, Indiana, and talked to Ed Kellar, the genealogy librarian, he logged me onto the Ancestry.com site. It’s a site I don’t typically use because, most of all, it requires a paid subscription. I was grateful for the opportunity.

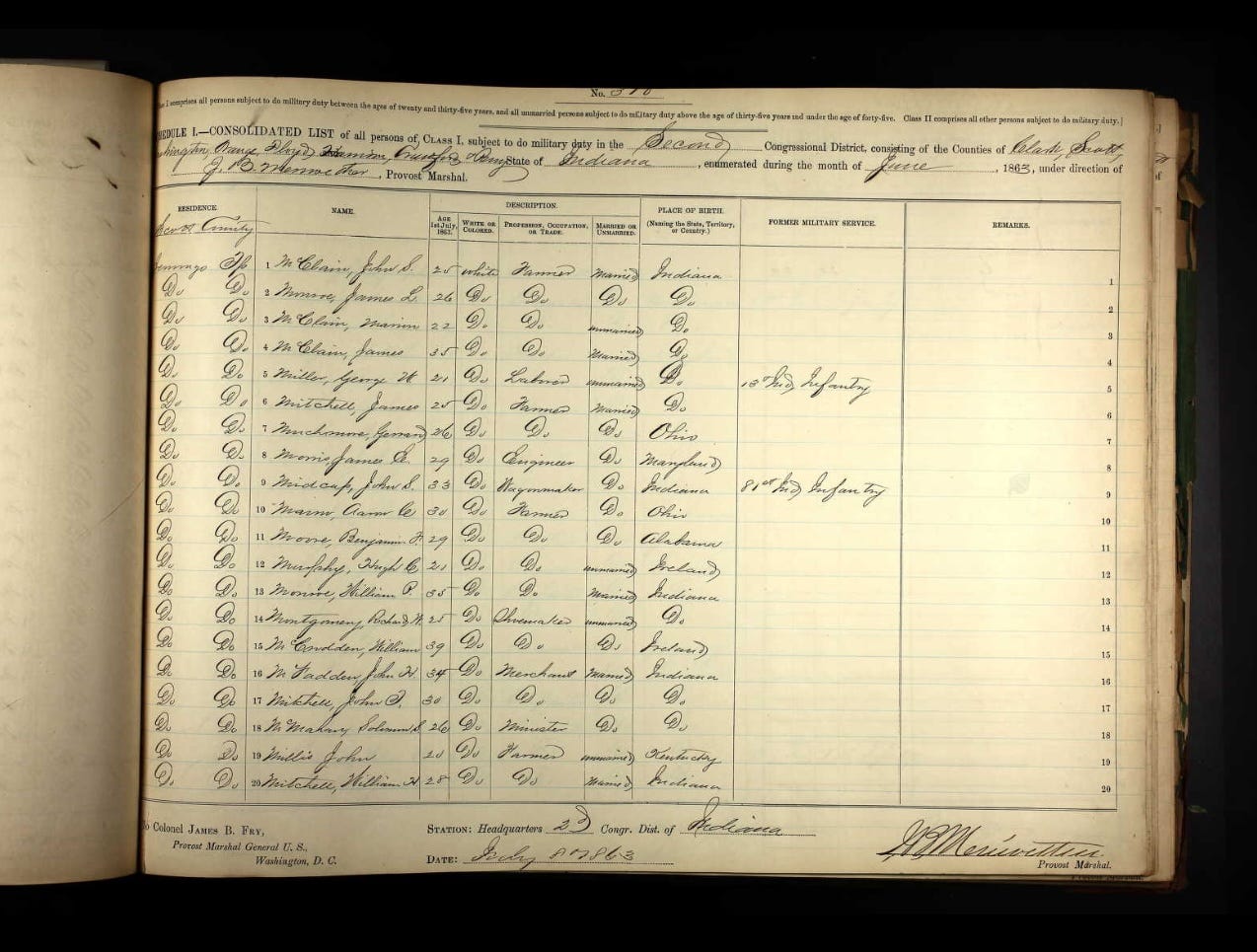

One of the most important things I found was a draft record in 1863—during the Civil War. There was James L. Monroe, which I first associated with Jennings County, but then realized was Jennings Township, Scott County. This James L. was 26, a married farmer, born in Indiana. This would put his birthday close to the 1836 date, rather than the 1841 date, the second of which more closely aligns with what I presume to be my third great-grandfather’s age.

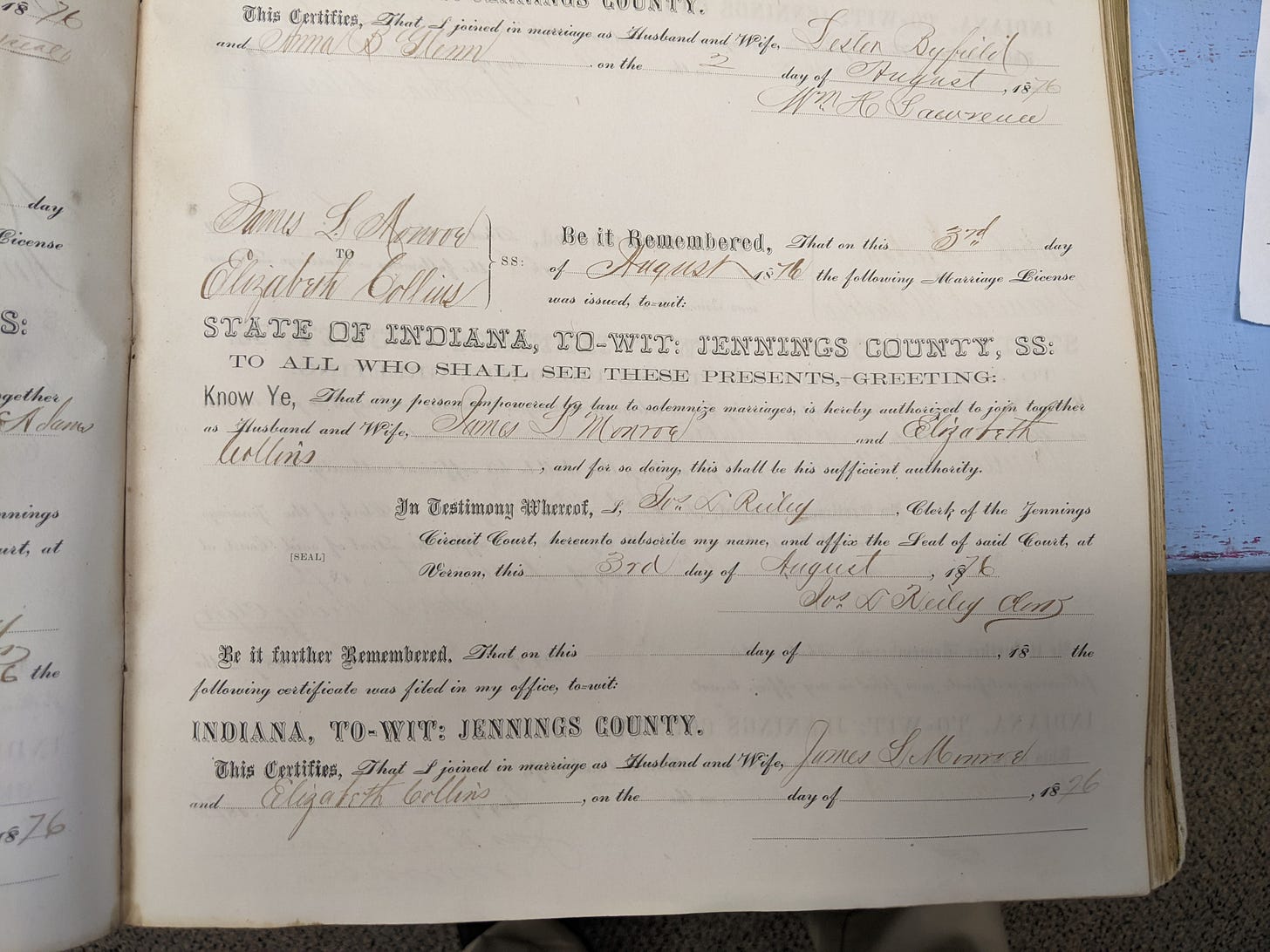

Seeing this, I began to think that there are simply two James L. Monroe’s at the time, and people today are confusing them. However, that may not be the case, either—although this “married” James L predates the wedding license I have for him marrying my third great-grandmother, Elizabeth—which occurred in 1876—I began to see that James may, in fact, have been married before.

That is, Elizabeth may have been his second wife. The way I discovered this was disturbing.

Because I’d learned previously that James and Elizabeth’s son, Lewis, my second great-grandfather, was born in Bartholomew County (according to his 1938 Social Security application), I reached out to Annette Blount, the Genealogy Librarian at the Batrtholomew County Public Library in Indiana, asking about the presence of the Monroes there. What she sent back astounded me.

What she found was, first, a clip from the Wednesday, August 29, 1894 issue of the North Vernon Plain Dealer. It was an obituary for James Monroe, under the heading of “Deer Creek.” Right off, I’d come to realize that Deer Creek, where his wife Elizabeth was said to be buried—and that came from both the Jennings County and State of Indiana death records—indicated not only a specific cemetery but a place. The fact that this James Monroe was there was too far from coincidence.

The obituary is simple: “James Monroe died suddenly Monday about noon. Funeral services Tuesday evening at 3 p.m. He leaves a wife and six children who have the sympathy of the community.”

The frustration, such as it is, lies in the fact that the middle name—or even just the initial—is missing. However, the six children, according to all the information I have, is the correct number: they are, from what I can tell, Lewis, Eliza, Marion, Edward, Delby, and Alta. However, there is one wild card: Missouri Monroe, a daughter, apparently, who appears on the 1880 census under James Monroe.

In that census, there are three children: Lewis is 3, and Eliza Ellen is 2. But there’s another daughter, “Missourie,” who is 15. It’s important to note that this older child is listed as a “daughter” specifically. And that, of course, means she was likely born before Elizabeth and James were married, or at least when it was recorded at the courthouse, on the 3rd of August, 1876. The census was recorded on June 11th, 1880.

Therefore, even if Missourie had been born, exactly 15 years before that, she still would have been born more than a year before the marriage. That seems unthinkable, given the times. This is another reason I suspect James had another wife, who perhaps died young, as well—maybe even during childbirth. In the 1880 census, James is 39; Elizabeth, 32—an age gap. I can see James being a father at 24, but Elizabeth would have been 17. It’s possible, but is it likely?

Further, strangely, Missourie is listed as living at the “Poor Farm,” so presumably she’s not in the house at all. Other records I’ve found indicates she’s there, as well.

In the 1900 census, Elizabeth is 53, and four children live with her: Marion, 19; Edward, 16; Alta, 13; and Dalby, 10. Lewis is grown and out of the house at 23 years old; in fact, his family entry is just below Elizabeth’s. The missing child is Eliza—indeed, Family Search shows no death date. There is no record of a wedding, either, which from what I’ve seen would have included her parents’ names. It’s possible she died young. This will matter later.

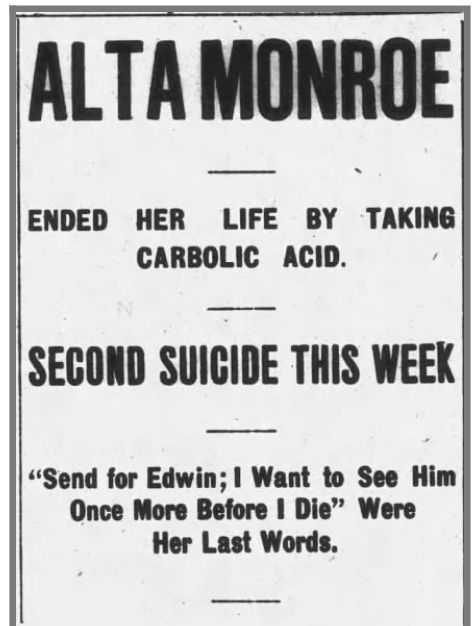

The final note is this: an article published on Thursday, September 29, 1904 in the North Vernon Plain Dealer, sent to me by Annette at the Bartholomew library. It is for Alta. She had committed suicide.

“‘Not wisely but too well’ was the way poor Alta Monroe loved Edwin Reynolds and suicide was the result,” it reads. It is worth quoting the entire article:

“He is a divorced man and utterly worthless. He began paying attention to Alta and won her love and confidence and it is reported that he had promised to marry her but recently had refused to do so. Trouble had been brewing between the two for some time although he still went with her. Tuesday she said to Mrs. Wm. Day, with whom she lived, ‘this is the last meal I’ll ever eat,’ but her remark was not taken seriously. She came down town in the evening and was in the company of three other girls. All seemed to be having a good time. She went home about half-past eight o’clock, entered the house and went to her room. In a few minutes she called Mrs. Day and said, ‘I am so sick.’ Mrs. Day leaned over her and smelled carbolic acid and saw a white streak on her cheek. She accused her of taking carbolic acid and she admitted that she had.

“Dr. Stemm, Dr. Green and Dr. Crouch were all summoned but before they arrived the acid had gotten in its deadly work. She became unconscious shortly after Dr. Stemm arrived. Her last intelligible words were: ‘Send for Edwin, I want to see him once more before I die.’ He came but she was unconscious. He had been drinking heavily and was in a maudlin condition, crying and bewailing her death. He was married a few years ago to a lovely girl in Vernon. He failed to support her and their child and about a year ago she procured a divorce from him.

“He can be summed up in two words, no account. The suicide was about twenty years old and an orphan and had never had a fair show in life. Only pity is to be felt for the poor unfortunate girl.”

The funeral had happened only the day before. Annette sent me another article, Alta’s obituary, published the same day in the same paper, that reads, “We desire to express our sincere thanks to our friends who so kindly assisted us during our sad bereavement.” It is signed by what I presume to be her four living siblings: Lewis, Marion, Ed, and Delby.

The obituary itself gives one more clue as to the family’s tangled history: “Miss Alta Amanda Monroe, daughter of James Lee and Elizabeth D. Monroe, was born near Hope, this county, July 19, 1886. She was a consistent member of the first Christian church, this city, having united with it in 1901. She departed this life Sept. 26, 1904, aged 18 years, 2 months and 7 days. Four brothers, one half sister and a host of friends survive her, her father and mother having recently preceded her to their Eternal Home.”

Her Indiana death certificate reads that her death was from “Carbolic acid poison administered by self.” She was, actually, eighteen years old; her birth was in July of 1886. The form was signed off by her brother, Marion.

Here I rest for the moment. I think about this list of names: the four brother’s names all appear on the obituary for Alta. I’ve connected them with James, in some cases, and Elizabeth in all. The half-sister, I’d guess, is Missourie, who perhaps had a mother who died young—someone on Family Search had made a connection to one “Dicey Monroe,” who appears in the 1850 census for Mercer County, Kentucky, possibly born in 1834, with a wedding record dated October 27, 1860 to one “James L. Monroe.”

Remembering that some documents claim James Lee was born in Kentucky, this marriage license may point to something, that “Dicey” was the mother of Missourie, who would have been born within, say three or four years of this marriage. There is no death date for Dicey.

Missourie married William Ross in Jennings County in 1888, with her father listed as “J. L. Monroe,” and her mother only as “D. Monroe.” Later, Missouri Ross appears on the 1900 census for Vernon, 39 years old, her birth date July of 1860 in Kentucky, with both of her parents born in Kentucky, as well. She’s widowed by then, a servant. It’s noted she can write but cannot read.

This dates her birth to around 1860 or ‘61, which sounds correct. The marriage of “Dicey Monroe” and “James L. Monroe” (cousins, perhaps?) dates, in Mercer County, Kentucky to October 27, 1860. The age on the 1880 census may be flat out wrong.

I wrote Ed Kellar about the obituary for James Monroe, asking if there were other papers in print at the time that might have carried an obituary. There were two, but only one, the North Vernon Sun, carried something. It was a simple paragraph:

“James Monroe, residing three miles east of the city, dropped dead Monday afternoon at his home, from heart failure. Deceased was about 55 years of age. Internment in the Vawter graveyard Tuesday afternoon.”

Measurement aside, the community of Deer Creek, which the other obituary noted, and where his wife, Elizabeth, is documented as being buried in, lies east of downtown. The 55 years dates his birth to 1839, yet another confusion—I wonder if people kept track of age at all. But most of all, there is the mention of the Vawter graveyard, which is today called Summerfield, and was once called, I’m told, Deer Creek. This was the cemetery I visited, and there was no stone I could find that would match these dates, though there was a “James” stone, but that seems to have been a child.

There are many loose ends, but a possible timeline is this: James Lee Monroe is born in Kentucky, perhaps Mercer County, in 1841. There, in 1860, he married Dicey, the daughter of a farmer, who may have been a cousin—not uncommon at the time. Soon after, they have a daughter, probably by the next year, named Missouri.

At some point, James Lee moves north with Missouri to Indiana, eventually settling in Jennings County. Dicey could have died by then, or else she died in Indiana. James may have been still married with his daughter in 1863, in Scott County, where he is registered for the draft. He remarries in 1876—this may account for his being older than his new wife, Elizabeth—and they take up a life of farming somewhere near the town of Hope. They have six children, and one dies young—probably later than 1894 but before 1900, I imagine. Missouri, by 1880, is sent to the poor farm; maybe they couldn’t take care of her.

Of the numerous dates given for James’s death—as early as 1894 in Deer Creek, or perhaps in 1895 at the poor farm in Vernon (though this seems unlikely) and as late as April of 1900—none are fixed yet. There are many James Monroe’s in this region of Indiana, and I’d need to spend some more time with the old newspapers in the county library, and probably go back to the health department to look at the death records closer.

It’s likely I’ll return to Jennings County again, and soon.

Great detective work! Sometimes it can take a while to gradually piece things together.