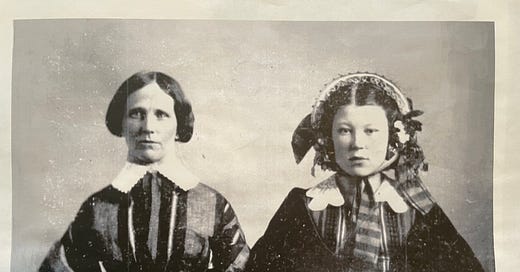

On the right, Julia Havens; with possibly her mother, Sabrina (or mother-in-law, Mary Rogers Hill), date unknown.

In doing research into my family past, I’ve often had this thought, one I’ll undoubtedly return to: it’s relatively rare to learn about the lives of women, especially as one goes deep into the past.

So what to do about this? Reconstruct as much as we can with what we have available. In this case, for me, I’ll talk about Julia.

Following back the threads of our people, we often come to end points, where our ancestors seem to emerge from nowhere. For me, it is a ferryman on the Farmington River in 1667. It is an orphan in London, the son of a sailor nearly lost to time, brought by ship to Boston following a plague. Or it is a villager from along the Rhine River, who crosses the Atlantic in the hull of a ship like the belly of the whale, where passengers died en route of starvation. Or an Irishman, a boxer, who was said to have escaped prosecution when he allegedly beat a man to death by coming to America.

What is utterly strange to me is to consider that, no matter how disparate these threads are, spread out over countries divided by seas and oceans, they all come to connect in me. Each of these lives ensured my own.

Recently, I was invited by

at to write a guest post where I thought about my third great-grandfather, Richard Lord Hill. When I finished, I got to thinking more about his wife, Julia Havens, who outlived him by decades. Who was she? Where was she from?Then I began to learn about Jesse Havens. The story, which is one of my origin stories, begins on an island.

Suffolk County, New York, stretches along most of the eastern portion of Long Island. At the far eastern edge, on the South Fork, between the Atlantic beaches and Peconic Bay, is the town of Southampton. The town was founded in 1640 by a number of families who’d crossed the sound from Connecticut—what must have been Puritans. In time, a whaling industry grew up there.

Jesse Havens was born in or near that village sometime around 1768. Of his family, I know nothing. His wife, Martha Goodale, is said to have been born on nearby Shelter Island, in either 1772 or 1774. Jesse and Martha were married about 1792 in Southampton, and then in about 1805 they left the island and moved far inland, into what is now upstate New York, to the Finger Lakes region.

They moved first to West Fayette, between Seneca and Cayuga Lakes. What drew them there is impossible to say. In 1806 they moved to Harmoneyville, then Hopeton in 1807 or 1808. I cannot find these towns on any map, though the names of roads testify to the existence of these places—the Hopeton Road, for example, leads to the cemetery of the same name, where these two are buried.

To the east of Hopeton, a distance of only a mile or two, is Dresden, where Jesse Havens built the first dwelling house in the area, a log cabin, in 1814. He worked as a ship carpenter, and he is said to have built most of the crafts that were used on the lakes in the early days, including the first boat ever launched onto Keuka Lake.

All of this information was given by his son, William Pomeroy Havens, to a reporter for the Geneva Courier in 1877 (he also recalled that the boatmen were paid fifty cents per barrel of flour they shipped to Geneva). William himself was born in Hopeton on October 30, 1811—he would have been a child living in a freshly built log cabin near the shore of Seneca Lake.

What amazes me is this: A little over 150 years after that cabin was built, I would myself be living as an infant in a house my parents rented in Watkins Glen, twenty-two miles south, at the head of the lake. And it is unlikely that my father—who is descended from the Havens—would have known this. His history was close at hand in regards to the map, and yet far from his mind.

Jesse died on February 27, 1837—he’s buried next to his wife who died two years later. In 1839, his son William removed to the village of Corning, which had only been founded two years before, and at some point he married Sabrina, whom at the moment I know nothing about save her name, which is carved on her stone in Hope Cemetery (though she may have been born Sabrina Tracy in Delaware County, and the death records indicate she died at age 54 in June of 1868).

It was in Corning, on June 26, 1840, that their second daughter, Julia, was born.

According to the Corning Journal, William had distinguished himself as a gifted sign painter for the Fall Brooks shops—”an artistic painter,” it read. He was working, apparently, even at the age of eighty (and his son, George, would go on to be a sign painter himself).

William died on June 7, 1898, at eighty-six years old, in his house on West Third Street. He’d been back in Corning since 1889, returning from a stint in Michigan. “He was a worthy man and much esteemed,” the obituary in the Corning Journal reads, “a very industrious man, and a very intelligent citizen” who had numerous friends. The editor of the Journal, in fact, had known him since boyhood.

Julia Havens, possibly by then Julia Hill; date unknown

Julia, his daughter, is someone I continue to research. In my post on Richard Lord Hill, her husband, I noted that his letters to her, written during their courtship before the Civil War, are kept among the collections of the State University of New York at Oswego, and I myself have digital copies. What do not exist, so far as I can tell, are her replies—none of Julia’s letters, so far as I know, exist.

What I do have is an article published in the Corning Evening Leader on the occasion of Julia’s 87th birthday. Her daughter, Helen, entertained on a Sunday afternoon, on June 26th, 1927. She had spent nearly her whole life in Corning by then—excepting twelve years in New York City—and in addition to her four children, she had sixteen grandchildren and eight great grandchildren—among them, my grandfather.

Her guests, according to the writer, congratulated Julia not only on her birthday but “the marvelous retention of all her faculties and her ability to enjoy life.” By then she didn’t walk much, but she did enjoy “motoring,” and she took a “keen interest in the life of today, both community life and happenings in the world at large.” She sang, at least at one point, in the choir of the First Presbyterian Church.

“She sews and tats,” the paper read, “with ability that would bring credit to much younger fingers. She is also much interested in reading. Her charming personality continues to make her well-liked both among her own generation and younger generation.”

She would outlive all of her siblings. Her brother George died of myocarditis in 1926, and her sister Helen died of a stroke in 1929. In 1912, her older sister Fannie, then deaf, was hit by a train in Corning when she was walking back from a shopping trip; she apparently never heard its approach. She was 72.

In the last three years of her life, she was confined to bed in her daughter’s home. She suffered a stroke in August of 1930—only forty years before I was born—and died on the thirtieth.

I imagine this woman, at the beginning of the Great Depression. Her husband had fought in the Civil War and nearly been killed. Her father was a professional sign painter, her grandfather a shipbuilder who’d come overland from a whaling village at the far end of Long Island. She lived to be ninety, spanning nearly a century of massive change in the country. What story did she tell herself? How did she think of her emergence from what might seem to us as humble beginnings?

In her childhood, the first wagon train left Missouri for California. The Mexican War erupted. The telegraph and sewing machine were invented. Slavery persisted and divided the nation. Her someday husband, and other relatives, would go to war over it.

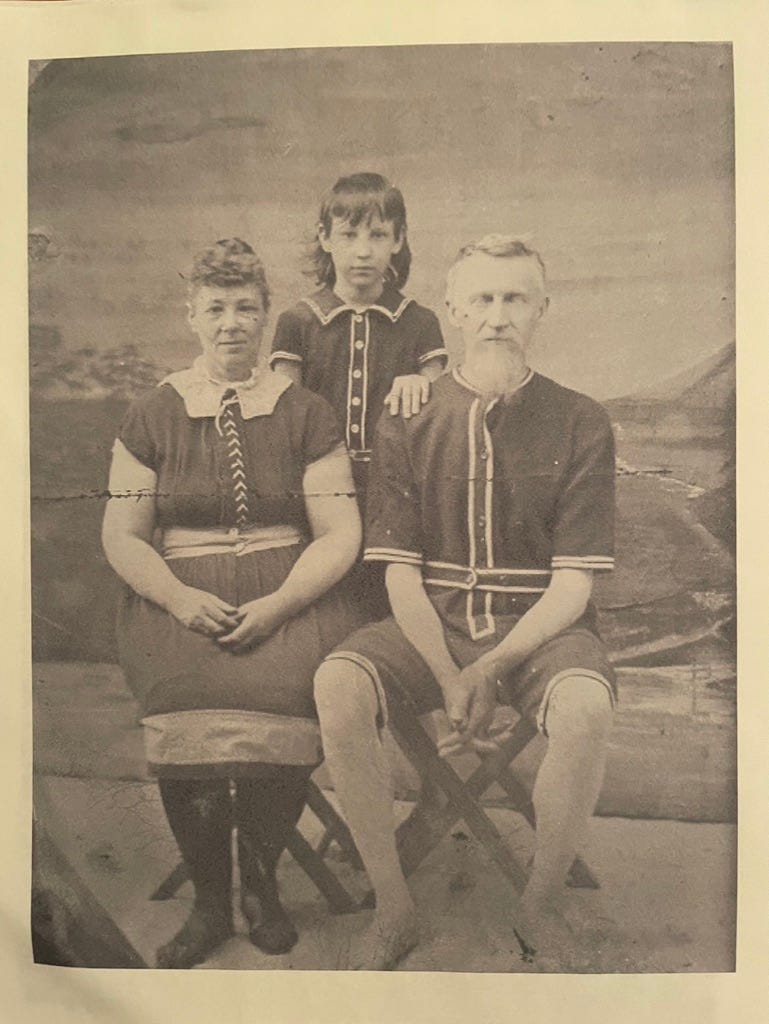

Julia and Richard Hill with unknown child, possibly a grandchild. Possibly 1890’s in New York City.

I am deeply aware of how difficult it is to learn about the women in my past. Julia is one, but there are many others who I have only the most cursory information for.

Recently, as I’ve been writing about my family, the Tombs, I might see in Philip Tome’s book that most of his story details the men’s exploits, but there is precious little about the women—including his own mother and sisters. Censuses, which began in 1790, for a long time only listed men; women and children were simply checkmarks in columns, denoted only by sex and age range.

If you are lucky—as I was with Julia—you may find at least something more than a name in a census that denotes a woman’s career oftentimes as “keeping house.” Online, I found a few characterizations of her from a letter written by, I believe, a granddaughter, posted on the Geni website, who remembered Julia as “rather stern,” perhaps owing to when her husband was away at war and she had to manage the household by herself. She would take her family to picnic on the lake—probably Waneta—though she herself could not swim.

She was afraid of thunderstorms, and would have her grandchildren get up on a bed and hold pieces of glass to ward off the lightning. Stockings were shocking to her. She herself wore “long voluminous skirts and high neck shirtwaists - with long, white aprons.” She was a good cook. And she was generous with the $50 or so that she received as a Civil War pension. The grandchild did not remember Julia talking about her husband at all. She did, however, see the Lincoln funeral train when it passed through Corning.

When she was old, she lived with her daughter Helen, bedridden on the second floor, and she would stamp her cane on the floor, calling to her daughter. When the daughter asked her what she wanted, Julia replied, “I just wanted to look at you.”

Below is a way for you to explore your own genealogies—especially, I hope, those of your grandmother’ grandmothers.