On a Saturday morning, last October, I left Louisville early and drove east toward Lexington on the interstate. The rising sun seared my eyes for miles. The Kentucky countryside rolled out its cloth, Shelbyville, Frankfort, a quick stop for gas at the truck stop at Waddy. I filled the tank and cued up Wilco’s Being There on Spotify and turned the stereo up as loud as it would go.

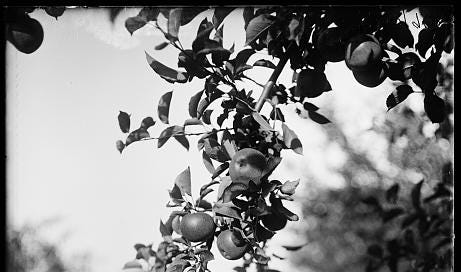

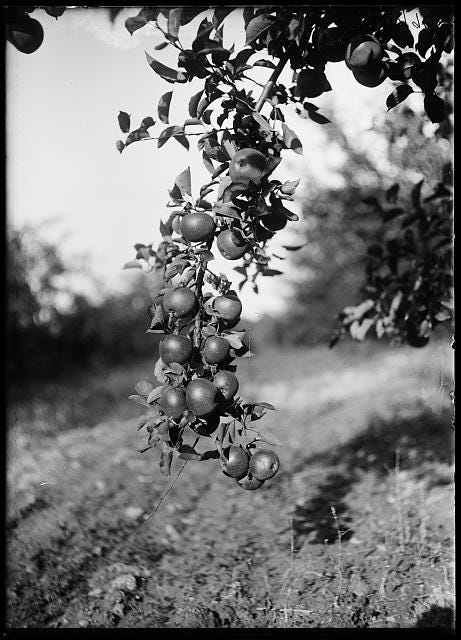

I was driving to Paris, Kentucky. There’s an apple orchard out there, the Reed Valley Orchard, which I’ve gone to many times over the years. In the early summer, you can pick blueberries, black raspberries. In the fall, apples and Asian pears.

I left the freeway and went north to Georgetown, then east again, past the college. At Centerville, I headed up the Russell Cave Road, then the Townsend Valley Road, then Lail Lane, narrow and often gravel, crossing the South Fork of the Licking River where it’s little more than a ditch. The orchard is at the end of the lane.

It was ten o’clock or so when I arrived. Not many people there that early. I pulled a wagon to the back rows and picked a few pounds each of Fujis and Cameos. It was late in the season, though even by then the Fujis, in particular, hadn’t fully ripened. I talked to another woman who told me that I could at least make pie or apple butter, though it would take more sugar than usual, Fujis being tart.

When I left, I followed Townsend Creek down the country road east to the store at Stepping Stone Farm to buy two gallons of apple cider, which is pressed nearby. I backtracked to Georgetown, parked on the edge of downtown and, sitting in my car, ate the yogurt and granola I’d packed with handful of blueberries. I walked the strip with my camera, the 35mm Minolta. I actually ended up meeting a photographer who had a small gallery down by the antique mall. I talked to her a while, and asked her how business was going. She told me that she was closing the gallery by year’s end; people just weren’t interested in fine art photography, she said.

I stepped out onto the street. How relaxing it is in the country. I had my cameras, some food, and time. It was only midday when I left for home—I had to mow the lawn, run a few loads of laundry, and go to the store for a few things before the new week began. But I felt, as I always do when I go out to the farms, that I’d made a kind of elemental run: I was returning home with a few negatives, some apple cider, and a few bags of apples I’d picked myself.

This was the life I wanted to live.

Think of your daily life. The little acts, the chores. The more I studied my ancestry, the more I’d find myself looking at my life as if someone else were watching, studying the way we lived from the far future. What would they think of this life? How archaic would it seem?

At home, they might imagine me bending over the sink to fill the water filter. The glass baking dish soaking—I’d cooked a meatloaf a few nights before. Where did I get that blue glass dish? My father, when I’d cleaned out his house in Corning after he died ten years ago? Or was it from my mother, when she had Parkinson’s? I can’t remember.

Some historian might imagine me bending to the bottom shelf of the pantry for my vitamins before I leave each morning for my job, teaching high school English up in Oldham County. There’s so much going on in the world, too: the floods in North Carolina, demolishing places I’d been to just this past spring, when I was visiting an uncle to interview him about his own grandfather; or the nearly 200 missiles Iran fired at Israel. Or the election cycle that year. The hurricane that just passed through Florida.

Now it’s mid-March, the weather growing more pleasant. The crocus are coming up, purple and yellow. Birdsongs increasing. A jambalaya is in the crockpot, jasmine tea in my porcelain cup. It’s Sunday afternoon, my daughter beside me on the couch, gaming on her phone. Tomorrow, I’ll drive her to school in the dark, then continue on the interstate to work.

I come home tired, often deflated. It’s unavoidable. I wake early most mornings, and am out of bed long before five if my mind will not quiet, running ceaselessly as it does over lesson plans I haven’t perfected, papers I may have forgotten to score, phone calls I have to make for appointments, and so on. The drive to work is a half-hour, but coming home is far different, nearly twice that as I fight through late afternoon traffic on a route that is tedious and serpentine to negotiate. When I arrive home, I chug perhaps a couple cups of green tea before making dinner. Sometimes there is laundry, schoolwork, and I squeeze in a walk when I can. Sometimes I even manage to exercise.

In the midst of all this, I sag in the evening. I tell myself, I’m writing a book. I insist, I am still a photographer. I have been working more on my book this year, daily in fact. And I’ve also been working in the darkroom, experimenting with lith printing. I find this a way to keep hope.

What would a historian make of all this? When I look back at my own ancestry, the farmers, the railroad workers, the glassworks foremen, the furniture makers, what did they feel? What were their doubts? Their fears? Were they as tired as I am?

Somewhere in the distance, I hear a helicopter. The street in front of my house is quiet. One morning in the autumn, I went outdoors in the dark to look at the sky. What I saw dwarfed me: the last quarter moon, Jupiter and Mars, Orion, Taurus, Sirius, Castor and Pollux. The quadrant of sky I would see all winter. I stood there in the street, looking up, craning my neck and trying to recapture the feeling of when I would look at the sky like this, what, thirty years ago now? Thirty years ago, when I lived in Oregon and had far fewer responsibilities.

Did my great-great-great-great grandparents do this, rising early on their farmsteads?

I had to leave for work. I could have sat outside for an hour, lying in the cool grass. But I went back inside to finish my coffee, to pack my lunch and satchel. Back to my paychecks, my vehicle, my mortgage, and my swelling student loan debt.

It was barely seven a.m. I was already tired.

I’m sitting on the couch, a Wednesday evening. The refrigerator—the one I bought last year when the old one started icing over daily—groans in the kitchen. I’m writing.

I make myself a plan for the month, using a daily organizer I keep as a PDF. I have a business plan I wrote as part of a consultancy I was awarded by the Commonwealth of Kentucky, the Arts Council—I get six hours of meetings with an arts professional, and due to my new schedule, it will be spread out over a year. I’ve been steadily writing essays to for Black and White Photography in England, and I’ll have at least two articles published in 2025. I have doctor’s appointments, forms to fill out, shopping to get done. The car probably needs oil by now, but I keep forgetting to check the dipstick.

In the midst of all this, I also want to drive to Western New York to visit an old friend of my mother’s, a Seneca Indian who lives on the Allegheny Reservation. I have an idea for another writing project, and I want to interview her. I thought to visit some cemeteries there, as well, where many of my German ancestors are buried. I could go see the house my grandfather grew up in out in Little Valley.

It’s a long days drive to Salamanca. Sure, I could stop in Cleveland, spend the night at my brother’s house east of the city, then continue on in the morning. I’d have two days to tour the Allegheny country, to stay with my mother’s friend—her name is Terry—and then turn around and go home, back to the job. I’m always fantasizing about winning the lottery. I never buy a ticket, though. I wonder why.

It’s a bit after nine, and I’m tired now. Soon I’ll set the laptop back on the desk and close it like a door for the night.

This is a meditation, nothing more. It is a way, really, for me to think on my identity, to clarify what I want.

When I took the teaching job and signed the year’s contract, I was troubled over many things. My debts, which include not only the student loans but the credit card—I was still paying back the trip I took to England with my daughter, and a few expenses from Sweden—not to mention my mortgage. This year, with property taxes going up, my escrow is again short. I needed health care, now that I was ineligible for Medicaid, and I needed, of course, my medication. I just needed money.

But there is a tradeoff, naturally. I give up a good deal of my time. Driving out to Paris, photographing up and down Main Street in Georgetown, wandering the orchards cradled in an oxbow of the Licking River, all this takes time. It is time well spent, and it brings me happiness, the actual feeling of happiness.

The evening I returned from Paris, after I’d napped, mowed the lawn, taken out the recycling, eaten dinner and washed the dishes, and after I’d put on a button-down shirt and a blazer and gone to an art show opening in Butchertown, followed by a run to Kroger for parmesan cheese and a box of Liquid IV packets, I went for a walk through the neighborhood.

I saw the gibbous moon in the twilight. A few people sitting outside the Old Hickory Inn, smoking. I passed the community gardens in Emerson Park, the big cottonwood tree in the alley off Forrest Avenue. And all the while I felt a joy seated in my chest. I think, as I always do, why is it so hard to keep?

Imagine all the things we could do if we didn’t have to participate in the economy. If we had no need of these objects kept in the drawers of our mortgaged houses. If we didn’t need to pay so much to change the oil, for our medications, for our plastic jars of parmesan cheese. I know it sounds foolish to even think this, and there is always the ghosts of my parents telling me I’m being impractical, unrealistic. Even irresponsible.

I come home to a book on how to write a business plan. I set it aside because I simply have words coming to mind the way I once saw the Sacramento River flowing out from a spring. I bent to the surge and held a jug to catch it, just as I do as a writer. Capture, contain. shape.

People will tell me that I’m doing good work, teaching students. It’s something I can do and even do well, something that I’m educated to do. I try to think of it as a “side-gig,” not a career. My career, I tell myself, is my writing, my photography. My art, in short.

Then I think, what isn’t art?