As my long-time readers know by now, I started teaching high school this year. I should say, starting teaching high school again.

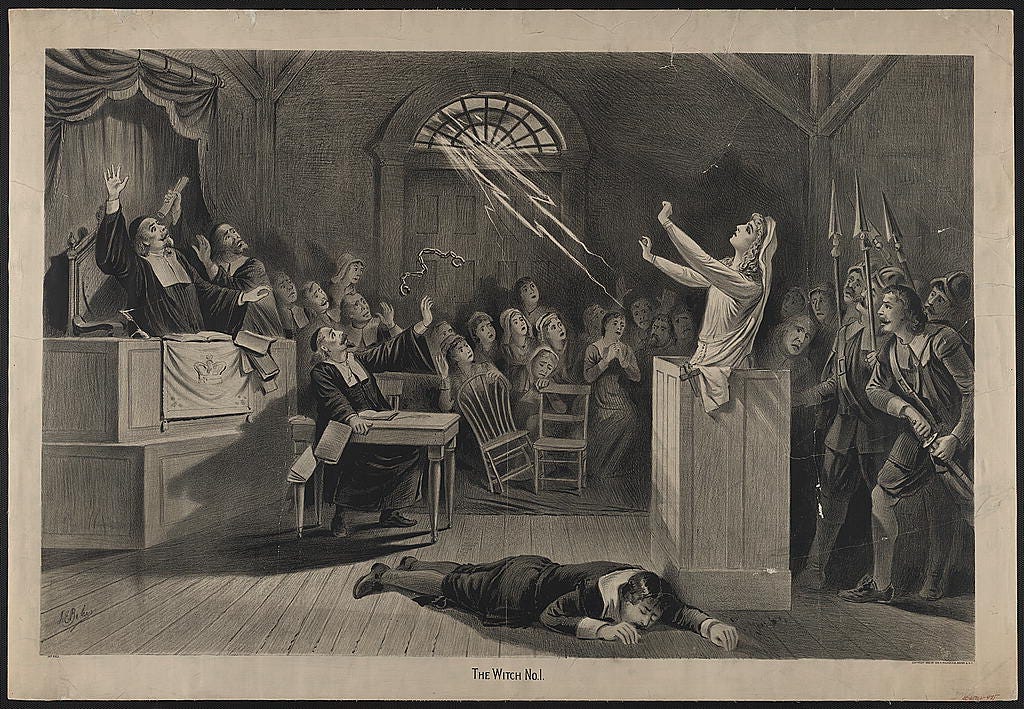

I first taught starting in 2001, and that year—and for three subsequent years—I taught junior English, one of my favorite classes: American lit. And for each of those classes, we read The Crucible, Arthur Miller’s classic critique of the social forces that led to McCarthyism and the Communist hysteria.

This year, I teach sophomores (another long-time favorite), so the teachers down the hall from me are taking on The Crucible. It’s been a delight to tell them that I learned recently that I’m descended from one of Salem’s accused—and convicted—witches.

My tenth great-grandmother, Mary Bradbury—born Mary Perkins in Warwickshire, England, where records indicate she was baptized on September 3, 1615—was convicted of witchcraft and sentenced to hang on September 9, 1692. The fact that she wasn’t hung—and there are numerous explanations as to how she escaped—marks her as the only accused witch to avoid execution.

Mary Perkins sailed for Massachusetts Bay on the first of December, 1630 (this date according to historian Gordon Harris), aboard the Lyon, which left from Bristol and arrived in Nantasket after some three months at sea. She would have been my daughter’s age, fifteen. There were somewhere around twenty passengers on the boat, including, apparently, the Reverend Roger Williams, a figure of note in New England history who would go on to see himself banished from Massachusetts but also become one of the founders of the Rhode Island Colony, where he would serve as president for a time.

Mary would have had, from what I can tell, a life of stature. Her father, John Perkins, quickly established himself in the colony. In May of 1631 he took the oath that made him a freeman. The family spent two years in Boston then removed to the new colony of Ipswich, founded in part by John Winthrop, the town Perkins represented in the General Court. There he would maintain several land grants, farming. His house stood near the river on what is now East Street, perhaps where the town wharf is now located.

In 1636, she married Thomas Bradbury, a land agent and one of the most distinguished men of Salisbury. Captain Bradbury had served as a magistrate—he confirmed land grants and was a highway surveyor—and he led a local militia.

According to the Salem Witch Museum in Massachusetts, Mary was actually known as Mistress Bradbury because of her standing in the society. Both “Goodwife” and “Goody” (and readers of The Crucible will recognize these terms), though terms of repute, still denoted women of less social standing.

In 1692, then, she would have been 77 years old (there’s some contention over her age, but I’ll go with this age, which was confirmed by Mary’s descendant, Martin Hollick, a reference librarian writing in 1997 for the Harvard Crimson). “She had been noted,” wrote Charles Upham in 1867, “through life, for business capacity, energy, and influence,” and by the time of the trials in 1692, she was “somewhat infirm in health.” At the time of the trials, she lived more than twenty miles from Salem Village.

One of the strangest things about the Salem trials—and it seems archaic and ignorant now, at least to me—is the admittance of what was called “spectral evidence.” This was legal evidence based entirely on the testimony of people who’d experienced visions, or claimed an accused witch had done them harm in a dream or a vision—and such evidence was made against Mary Bradbury.

Victims of witchcraft claimed to have seen spirits, and the fact that the courts and judges believed them seems, at first glance, ludicrous. It could have been mass hysteria, and such beliefs were certainly to be attributed to religious beliefs at the time. Mary, for example, was famously said to have turned into a “blue boar” and attacked George Carr’s horse and causing, later, another Carr’s death. Weirdly, this incident had happened years before—in 1679.

During the trial, Richard Carr, the son of George, claimed that “Mrs. Bradbury, the prisoner at the bar, upon a sabbath at noon, as we were riding home, by the house of Captain Thomas Bradbury, I saw Mrs. Bradbury go into her gate, turn the corner of, and immediately there darted out of her gate a blue boar, and darted at my father’s horse’s legs, which made him stumble; but I saw it no more.”

But there is more to this story than a weird occurrence. Consider, in the original language, this document, another accusation against Mary Bradbury:

"Certaine Detestable arts called Witchcraft & Sorceries Wickedly Mallitiously and felloniously hath used practiced and Exercised At and in the Township of Andivor in the County of Essex aforesaid in upon & against one Timothy Swann of Andivor In the County aforesaid Husbandman – by which said Wicked Acts the said Timothy Swann upon the 26th day of July Aforesaid and divers other days & times both before and after was and is Tortured Afflicted Consumed Pined Wasted and Tormented, and also for Sundry other Acts of Witchcraft by the said Mary Bradbury.”

Among the witnesses who signed this document was Ann Putnam—a name readers of The Crucible will recognize. This Ann, in fact, was the child of the elder Ann Putnam—who was born Ann Carr. And her husband, Thomas Putnam, was the one who recorded these depositions for the court.

It turns out there was a longstanding feud between these two families, the Carr’s and the Bradbury’s. And at least some of it was rooted in, if we are to believe some of the writers, unrequited love.

More next time.

Fascinating background info, especially since my husband is also a descendant of Mary Perkins!

In a recent gathering of #GenStackCoterie, talk turned to how many of us have “witch”stories in our families and that we should start an anthology!

Great work, cant wait to learn more!