Two of my ancestors, husband and wife, are buried in a cemetery that bears the name of a village that no longer exists, and hasn’t existed for more than 150 years.

This graveyard, the Hopeton Corners Cemetery, is located on a bluff above a river. The town, Hopeton, once stood at a crossroads on what is today New York State Highway 54, which connects the village of Dresden to the town of Penn Yan. The mills, which also wore the name of Hopeton, were just south of here, but they too are gone. Not even ruins remain.

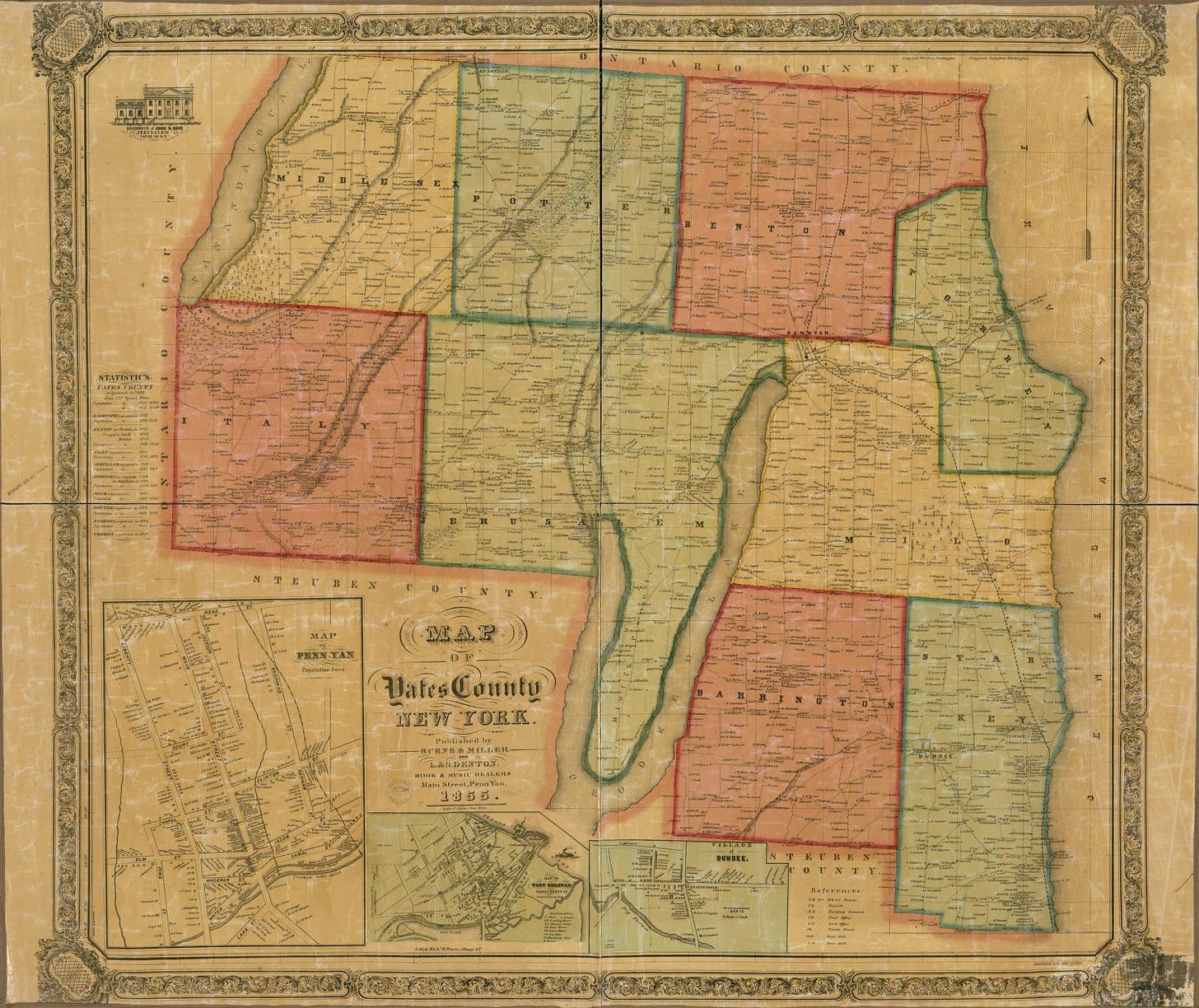

This area lies in the town of Torrey, in Yates County. The History and Directory of Yates County, published in 1873, gives an account of what was once known to white settlers as the Genesee Country. This was the land of the Senecas, whose word, Genesee, meant “the beautiful valley.”

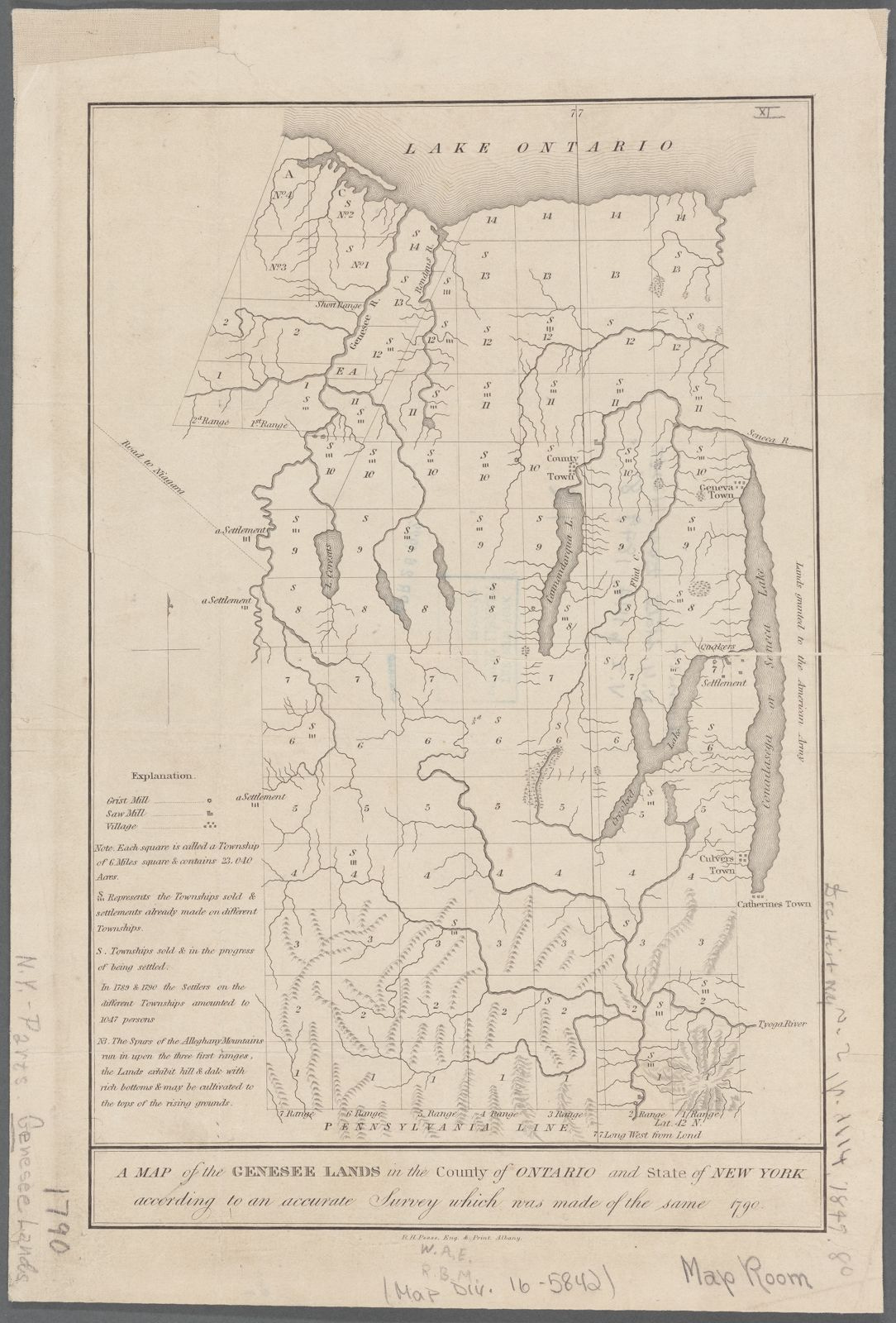

The land in question lies between Keuka Lake—it was once called Crooked Lake, as a map from 1790 indicates—and Seneca Lake, two of the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. Over a period of years, a number of borders and municipalities were imposed upon this landscape that was, as we might imagine, a wilderness still in the late eighteenth century, in the years following the American Revolution.

It was, as the book notes, “an unbroken forest.” It was into that frontier that my ancestors came.

They began in Suffolk County, at the far eastern end of Long Island, in the town of Southampton, which the town proudly claims as the first English settlement in New York. Founded in 1640 and located on the Atlantic, the colonists soon founded a whaling industry that lasted well into the nineteenth century.

Beginning in 1874, William S. Pelletreau, who began serving as the town clerk in 1861, oversaw the publication of several volumes of the original town records, going back as far as 1639. In the first volume, I find two names: Joseph Goodale and D. S. Havens.

Birth records are scarce in these books, and unfortunately nonexistent for these two men—and for the most part, early American documents are the records of the transactions of men—but several generations later, there are two people reputedly born here: Jesse Havens and Martha Goodale.

Jesse, said to be born in 1768, was a shipbuilder, a sensible occupation in a town founded both on fishing and whaling. Martha was born in 1774 to what was likely a prominent family—their names appear often in early records. The two married in 1792.

Why they left Long Island is anyone’s guess. The town may have been crowding, but more likely it was the fact that land purchases in the frontier of New York—the Finger Lakes, in particular—was seen as opportunity. They left probably in 1805, arriving first in West Fayette in Seneca County, and in the next year in Harmonyville, to the west of Keuka Lake. They would have left with their firstborn son.

They settled, in either 1807 or 1808, in the village called Hopeton—it is said to have appeared occasionally on early maps as Hope. In this “unbroken forest,” clearings were few. Indeed, the map of 1790 shows very few settlements—and some of those settlements were Seneca villages.

Jesse carried on his shipbuilding here. His second son, William Pomeroy Havens, was born in Hopeton in 1811. Within a few years, in 1814, his father built the first log cabin in what would become the village of Dresden, closer to the shore of Seneca Lake. An interview with William in the Geneva Courier of November, 1877 says that “Mr. Havens is full of reminiscences when the village was new.” His father, William related, “long followed the business of a ship carpenter. He built most of the crafts which in the early days was used on the lakes.” He built the first boat on Keuka Lake, his son recounts.

By the time Jesse died in 1837, the village of Dresden—which sat squarely on the lakeshore—was drawing the industry and businesses from the countryside. Hopeton began to shrink. Today, nothing of it remains. It continued to appear on maps in 1855 and 1865, but by the time the Civil War passed, the town had vanished. The only memory of it is in the names of the Hopeton Road and the cemetery, which seems, for the most part, unmarked and invisible from the road.

No wonder, then, that when William married—to Sabrina Tracy in February of 1836—it was in the town of Dresden. His first daughter, Fannie, must have been born there, as well.

The year Martha Havens died, 1839, William left Dresden, the Town of Torrey, and Yates County and went south with his family to a village that had been founded only two years before: Corning. He was a sign painter, ultimately working in the shop of the Fall Creek Railroad. Apparently, he was quite gifted.

The year after his arrival, on June 26, 1840, his second daughter, Julia Alice Havens, was born. She is the first generation to be born in Corning, New York. I am the sixth.

William left for Michigan for a time, though I’m not sure how long. He returned ultimately to Corning. In the 1890’s, several articles were printed in the Corning Journal about him. “The writer of this has always known him,” an 1894 edition read, “and takes pleasure in saying that as a man and citizen he has ever been worthy of respect.”

In 1898, the paper published his obituary. “He was an artistic painter, and had no equal in sign painting,” the obituary reads. “He was a very industrious man, and a very intelligent citizen and had numerous personal friends. The editor of the Journal had known the deceased from his own early boyhood and esteemed him highly.”

His daughter, Julia, came up from New York City before he died. Her husband, Richard Lord Hill, arrived for the funeral. William was eighty-six when he died. He was buried in Hope Cemetery on South Corning Road. The stone is a simple one, smaller than one might expect of “a first-class painter.” He is buried beside his wife who died thirty years before.

Julia may never have seen the Hopeton country. Her grandparents died before she was born, and William may never have returned to Dresden for a visit. It’s hard to say. I wish I had diaries or letters written by Julia. Perhaps there once were.

I’ve written about the Havens line before on this platform. I’ve revisited because I’m working on another chapter of my manuscript, and I’ve decided to start here. I’m trying to open my story cinematically, with a wide view of this Genesee country, and also the Concanoga, “the land of the three rivers,” which is what the Seneca called the valley where Corning was built. I am looking at the landscape as if I were writing a myth, even a fairy tale. What is this place? What was here before me?

I’ve been struggling with these words for weeks. I wake early, before I begin getting ready for teaching, before my daughter is awake, and I try to eke out a few more words, a few good sentences. All the while I ask myself, but what am I trying to say?

There is something stunning in the idea that a village—it once hosted, in addition to many houses, a tavern and a toll booth, and had its own post office—could simply vanish. And that it happened in a land that was wrenched from Seneca. I am particularly irritated to think of it, to think of all of upstate New York, where I grew up, as once an “unbroken forest.” I remember my uncle pointing this out to me: that for the most part, all of what we could see in the hills around us, the hills around Corning and the “three rivers,” were not the original forest, that it was all, at one point, cut down, the hills bare and barren.

And then there is the question of what we do with this history. Why is it valuable to know this? What do I want to convey by relating what I can see in the old histories as an accounting book of losses: the Seneca, along with all their names for these places, the forest, even the first settlements. We sent troops into that forest to destroy the villages of the Seneca, and for what? To build villages that vanish?

Even Dresden, which like a magnet pulled all the town’s industry toward the lake—what’s there now? A trail along the Keuka Outlet. A restaurant, a winery, a brewery. The Robert Green Ingersoll Birthplace Museum. A Methodist church. A post office. Then there are the usual small town businesses, mostly at the edge of town: gun shop, a garage, boat repair, farm equipment.

To understand this place, which is remote to me, I know I’d have to travel there. I’d like to see the graves for myself, and to stand at that crossroads on the Hopeton Road. I imagine myself telling the stories of these people to locals who may inquire as to why I might be standing on the side of the road, looking into the past. Or, standing beside a few humble graves, pointing my camera.

I might say, this is where I began. And I wanted to find the root. I wanted to talk to ghosts—not only these people, but of the villages themselves.

Three days ago I started researching Napoleon, AR which disappeared when the Mississippi moved. I love serendipity 😉

Fascinating. Saved to read again more slowly later.